Translate this page into:

Significance of finding benign endometrial cells in women 40–45 versus 46 years or older on Papanicolaou tests and histologic follow-up

*Corresponding author

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

The 2014 Bethesda System recommends reporting the finding of benign-appearing, exfoliated endometrial cells on Papanicolaou (Pap) tests in women aged 45 years and older. We aimed to determine the significance of normal endometrial cells on liquid-based Pap tests in women aged 40 years and older and to correlate this finding with clinical factors and cytologic/histologic follow-up.

Materials and Methods:

We retrospectively identified all women aged 40 years and older who had benign endometrial cells (BECs) on Pap tests at our institution during a 6-year period. Histologic follow-up and outcomes were evaluated.

Results:

Among 18,850 Pap tests during the study period, 255 (1.4%) had findings of BECs and 159 (62.4%) of these women had follow-up Pap tests or subsequent tissue sampling by surgical procedures. Of the 159 cases, only 4 (2.5%) had significant endometrial pathologic processes, all endometrial endometrioid adenocarcinoma (three women had postmenopausal bleeding and 1 was perimenopausal with menorrhagia). No women between ages 40 and 45 years had significant pathologic findings and only one woman between 46 and 50 years (47 years) had an endometrial endometrioid carcinoma (1.5%). Women older than 47 years have higher odds (5.38) of having a significant endometrial lesion (P = 0.029) than those who are ≤47.

Conclusion:

Clinically significant endometrial lesions occurred predominantly in women older than 50 years (4.6%) and in only one woman between ages 46 and 50 years (1.5%). Therefore, endometrial sampling should be performed in women aged 47 years and older with BECs, especially when additional clinical indicators (e.g., postmenopausal bleeding) are recognized.

Keywords

Benign endometrial cells

histologic follow-up

Papanicolaou test

INTRODUCTION

The presence of benign endometrial cells (BECs) on cytologic analysis has been linked to significant endometrial disease in women older than 50 years who are noted as postmenopausal and may have clinical symptoms such as postmenopausal bleeding.[1234567891011] To date, the Papanicolaou (Pap) test is still the most cost-effective and successful screening tool for cervical dysplasia and carcinomas.

Initially, the 1991 Bethesda System and atlas for reporting cervical cytologic findings recommended that cytologically benign-appearing endometrial cells are reported in postmenopausal women as an “epithelial cell abnormality.”[41213] This was mainly because a small percentage of postmenopausal women with endometrial cancer had no clinical symptoms such as vaginal bleeding.[1213] However, in 2001, the Bethesda System changed such that age instead of menstrual status was the determining factor when reporting BECs, mainly because of lack of clinical information or history or incorrect information available to the laboratory.[413] The age for reporting exfoliated BECs was set at 40 years and older.[271213]

Several studies noted that this change caused a significant increase in BEC cytology reporting (9-fold in one study) and a significant increase in follow-up endometrial sampling.[7] Many authors reported that even with the increase in endometrial biopsies and curettages, the incidence of atypical endometrial pathologic findings did not increase.[714] On the basis of numerous studies and a collaborative effort of many medical professionals, the 2014 Bethesda System raised the suggested minimum patient age for reporting exfoliated BECs from 40 to 45 years. However, the actual incidence of pathologic findings in women younger than 50 years with reported BECs is still not clear.

The primary aim of the study was to examine the impact of age, menstruating status, and abnormal bleeding on the outcome of endometrial lesion in patients with normal BECs detected on annual Pap smear screening.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient selection

The study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board, was compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, and the need for informed consent was waived. We retrospectively searched our anatomic pathology database for the records of all women aged 40 years and older who had a Pap test at Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Florida, from January 1, 2010, to December 31, 2015, and for whom their Pap test results showed “normal BECs.” We excluded all patients who had a concurrent high-risk lesion such as low-grade or high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion, atypical squamous cells, or atypical glandular cells.

Data collection

Clinical data were collected from the medical record including age at diagnosis, date and details of initial Pap test, date and details of subsequent follow-up procedures (follow-up Pap test, endometrial biopsy and curettage, hysterectomy, cervical biopsy, and endocervical curettage), and clinical history and clinical indication for the follow-up procedure. All Pap test specimens were prepared using the SurePath liquid-based Pap test (Becton, Dickinson and Company), which is the only method used in our institution. All follow-up specimens (biopsies, curettage, and hysterectomy) were stained using the conventional hematoxylin and eosin method. A diagnosis of BECs was made based on the finding of three-dimensional clusters with small, round nuclei, indistinct nucleoli, and scant cytoplasm with indistinct cell borders.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were reported as mean (standard deviation) and median (range) and categorical variables were summarized as frequency (percentage). Continuous variables were compared between the patients with and without endometrial lesion using Wilcoxon rank-sum test and categorical variables were compared with Chi-squared test. Univariate logistic regression models were used to identify any association between clinical factors (age, abnormal uterine bleeding, and menstrual history) and a significant endometrial lesion outcome (disordered proliferative endometrium, benign endometrial polyp, and endometrial adenocarcinoma). All tests were two sided with alpha level set at 0.05 for statistical significance.

RESULTS

Among 18,850 Pap tests during the study period, 255 (1.4%) showed BECs. The median age of these 255 women was 48 years (range, 40–88 years). Of the 255 women, 159 (62.4%) had follow-up with either Pap tests (n = 54; 33.9%) or subsequent tissue sampling by surgical procedures including endometrial biopsy (n = 80; 50.3%), endometrial curettage (n = 13; 8.2%), hysterectomy (n = 7; 4.4%), cervical biopsy (n = 3; 1.9%), or endocervical curettage (n = 2; 1.3%).

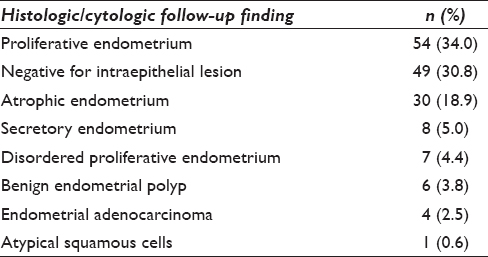

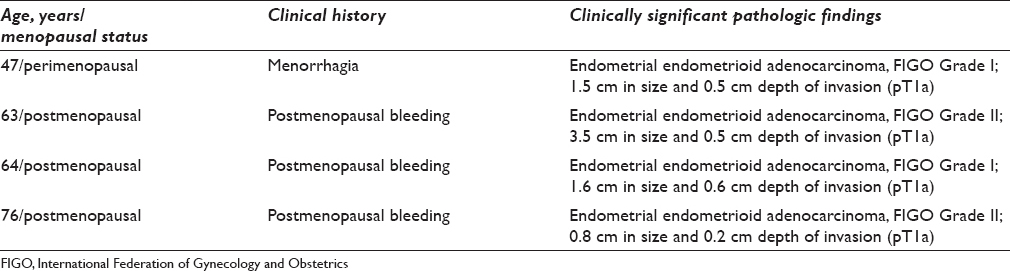

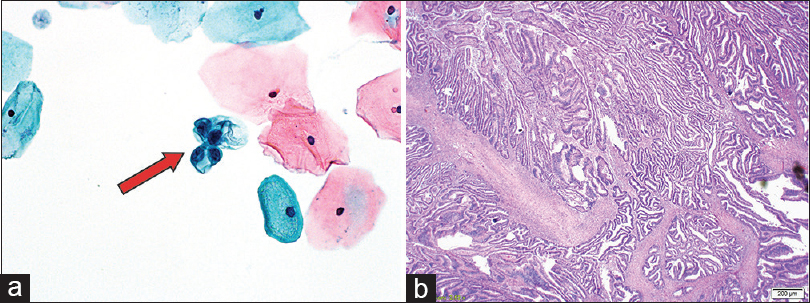

Among the 159 women with follow-up, 27 were aged 40–45 years (17.0%), 67 were 46–50 years (42.1%), and 65 were older than 50 years (40.9%). Thirty-seven women were postmenopausal (23.3%), and the median time to follow-up testing after an initial diagnosis of BECs was 39 days (range, 1–2690 days). The clinical indications that prompted a follow-up evaluation after the diagnosis of BECs are shown in Table 1. The pathologic findings on follow-up were benign in the majority (n = 155; 97.5%), which included atrophic endometrium, proliferative/secretory endometrium, endometrial polyp, and disordered proliferative endometrium [Table 2]. The other four cases (2.5%) were found to be endometrial endometrioid adenocarcinoma (3 women had postmenopausal bleeding and 1 was perimenopausal with menorrhagia) [Table 3]. Among the 27 women between 40 and 45 years, none had significant pathologic findings, 13 had benign endometrium, and 14 had normal follow-up Pap test results. Only one woman out of 67 between ages 46 and 50 years (age 47 years) had an endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma (1.5%), which was International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics Grade I [Figure 1]. The other three women with endometrial endometrioid type adenocarcinoma were older than 50 years (4.6%), all of whom had postmenopausal bleeding [Table 3]. The difference between finding a pathologic lesion in women aged 40–50 years (1/94, 1.1%) compared with women older than 50 years (3/65, 4.6%) was not statistically significant (P = 0.31).

- Histologic results in a 47-year-old female. (a) Liquid-based Papanicolaou test with a rare cluster of benign endometrial cells (arrow) (×20). (b) Hysterectomy specimen with International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics Grade I endometrial adenocarcinoma arising in a background of atypical complex hyperplasia (H and E, ×10)

Logistic regression model did not reveal that any of the clinical variables (age, abnormal uterine bleeding, menstruating status, and days to follow-up) are statistically significant [Table 4]. However, average age was higher for patients with an endometrial lesion (average age is 51; Table 4), and particularly, patients over 47 had higher odds of having an endometrial lesion compared to age ≤47 [Table 5]. However, as a continuous variable, age was not a significant predictor [Table 5].

DISCUSSION

Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic cancer in the United States, the incidence of which is increasing along with the aging population.[2] Most endometrial cancer is diagnosed in women older than 50 years.[2] Normal-appearing endometrial cells may be shed in the second half of the menstrual cycle or in the postmenopausal period when physiologic shedding is not expected to take place.[2614]

Our study showed that the finding of BECs in Pap tests is uncommon (1.4%). BECs were not associated with any significant pathologic processes in women between ages 40 and 45 years, and pathologic lesions were not significantly more common in women younger or older than 50 years. However, most of the significant pathologic findings, including endometrial adenocarcinoma, occurred in women who are 47 years or older and who had an associated important clinical finding such as postmenopausal bleeding.

Normal endometrial cells on Pap tests have been associated with variable benign and malignant diseases including endometrial polyps, endometrial hyperplasia with and without atypia, endometrial carcinoma, leiomyoma, atrophy, proliferative endometrium, and intrauterine device use.[6815161718] Previous reports have suggested that a finding of BECs on Pap tests is clinically significant and warrants further evaluation because some of these patients may have endometrial carcinoma or its precursor (e.g., nonatypical and atypical hyperplasia).[361718] Of interest, in a study from 1999, before the 2001 Bethesda guidelines were implemented, only one patient younger than 50 years was classified as having a significant endometrial pathologic process (complex hyperplasia with atypia) on histologic follow-up.[3] The patient was 45 years old with a cytologic diagnosis of BECs and a clinical history of postmenopausal bleeding.

Several early retrospective studies investigated the prevalence of endometrial pathologic processes among women with BECs on Pap tests.[1920] One study found a 17% incidence of endometrial hyperplasia or adenocarcinoma among women aged 40 years and older with endometrial histologic follow-up.[20] Since these studies were published, and until the mid-2000s, the rates of hyperplasia and malignancy associated with BECs on Pap tests have decreased.[215] The reason for this may be the increased use of hormonal replacement therapy for menopause-related symptoms at that time[24] – the rates of BECs on Pap tests are higher among women receiving estrogen supplements.[2716]

In one study, menopausal status was a significant independent predictor of the clinical significance of BECs.[17] Another review study concluded that older age is an independent predictor of endometrial pathologic processes.[2] Complementing these findings are others showing that cancers were only noted in women older than 45 years,[18] and that cytologic diagnosis of BECs in premenopausal women older than 40 years alone is clinically insignificant.[616] Another study in women with BECs on Pap tests reported significant endometrial pathologic findings in only one of 96 premenopausal women aged 40 years and older (1%), compared with 10 of 130 postmenopausal women (7.7%).[21] The authors suggested that reporting findings of endometrial cells on Pap tests in premenopausal women aged 40 years and older “have no clinical relevance.”[221]

A study by Gomez-Fernandez et al.[5] included 44 asymptomatic women with BECs; these patients had no endometrial biopsy, and no pathologic processes were detected on follow-up of 3–6 years. In addition, all subsequent Pap tests were negative, and clinical histories and physical examinations were unremarkable.[5] The authors concluded that reporting the presence of BECs in Pap tests of asymptomatic women is of no significance for clinical management in those patients. Our study showed that no women between ages 40 and 45 years had significant pathologic findings, and only one woman between 46 and 50 years (who was 47 years old and symptomatic [menorrhagia]) had an endometrial endometrioid adenocarcinoma.

Our current findings are similar to those of other studies,[14589101121] in which reporting of BECs in women younger than 45 years is of no clinical relevance,[6] and significant endometrial pathologic findings were noted in women older than 50 years.[21011] Moreover, significant endometrial pathology was found in postmenopausal women, especially those receiving hormonal therapy.[23716]

Our study has a few limitations including retrospective selection of women who had a diagnosis of BECs on Pap smear testing. In addition, follow-up endometrial sampling or repeat Pap testing was not performed for 96 women (37.6%).

CONCLUSION

Clinically significant endometrial lesions occurred predominantly in women older than 50 years (4.6%) and in only one woman between ages 46 and 50 years (1.5%). Therefore, endometrial sampling should be performed in women aged 47 years and older, especially when additional clinical indicators (e.g., postmenopausal bleeding) are recognized. With the many changes in health care, and the consistent discussion of health care-related costs in the media, health professionals must make conscious efforts to provide the best possible diagnosis, and treatment for their patients without adding unnecessary risk, cost, and procedures or causing undue anxiety.[8] Therefore, many determining factors should be considered when reporting BECs and when determining whether follow-up is necessary for asymptomatic perimenopausal women younger than 50 years.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

There are no competing interests as reported by all authors.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors have equally contributed to the conception, design, data collection and analysis, and draft writing and final draft approval.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors have followed the ethical guidelines for Human subjects research according to the declaration of Helsinki and institutional review board.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS (In alphabetic order)

BEC - Benign endometrial cell

Pap - Papanicolaou.

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double-blind model (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

REFERENCES

- Significance of benign endometrial cells in Papanicolaou tests from women aged >or=40 years. Cancer. 2005;105:207-16.

- [Google Scholar]

- The significance of benign endometrial cells in cervicovaginal smears. Adv Anat Pathol. 2005;12:274-87.

- [Google Scholar]

- Significance of benign endometrial cells in Pap smears from postmenopausal women. J Reprod Med. 2001;46:795-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- In Papanicolaou smears, benign appearing endometrial cells bear no significance in predicting uterine endometrial adenocarcinomas. Diagn Cytopathol. 2013;41:335-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reporting normal endometrial cells in Pap smears: An outcome appraisal. Gynecol Oncol. 1999;74:381-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Histologic follow-up in patients with Papanicolaou test findings of endometrial cells: Results from a large academic women's hospital laboratory. Am J Clin Pathol. 2012;138:79-84.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Bethesda System 2001 recommendation for reporting of benign appearing endometrial cells in Pap tests of women age 40 years and older leads to unwarranted surveillance when followed without clinical qualifiers. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;107:86-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Routine endometrial sampling of asymptomatic premenopausal women shedding normal endometrial cells in Papanicolaou tests is not cost effective. Cancer. 2007;111:26-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Normal endometrial cells in liquid-based cervical cytology specimens in women aged 40 or older. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;105:672-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical significance of benign endometrial cells found in Papanicolaou tests of Turkish women aged 40 years and older. J Cytol. 2013;30:156-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Age cut-off for reporting endometrial cells on a Papanicolaou test: 50 years may be more appropriate than 45 years. Cytopathology. 2016;27:242-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Normal-appearing endometrial cells in Pap tests of women aged forty years or older and cytohistological correlates. Acta Cytol. 2015;59:175-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Pap test and Bethesda 2014. “The reports of my demise have been greatly exaggerated.” (After a quotation from Mark Twain) Acta Cytol. 2015;59:121-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reporting endometrial cells in Papanicolaou smears of women age 40 and older: A qualifying educational note could prevent unnecessary follow-up biopsy. Acta Cytol. 2007;51:178-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytologically benign endometrial cells in the Papanicolaou smears of postmenopausal women. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;80:37-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- Significance of “normal” endometrial cells in cervical cytology from asymptomatic postmenopausal women receiving hormone replacement therapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;81:33-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Significance of cytologically normal endometrial cells in cervical smears from postmenopausal women. Acta Cytol. 2001;45:153-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- The clinical significance of benign-appearing endometrial cells on a Papanicolaou test in women 40 years or older. Am J Clin Pathol. 2005;124:834-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Significance of endometrial cells in the detection of endometrial carcinoma and its precursors. Acta Cytol. 1974;18:356-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- Significance of endometrial cells in cervicovaginal smears. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 1977;7:486-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reporting endometrial cells in women 40 years and older: Assessing the clinical usefulness of Bethesda 2001. Am J Clin Pathol. 2005;123:571-5.

- [Google Scholar]