Translate this page into:

Teenage cervical screening in a high risk American population

*Corresponding author

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

The new 2009 ACOG guideline for cervical cytology screening changed the starting age to 21 years regardless of the age of onset of sexual intercourse. However, many recent studies have shown a dramatic increase in the incidence of cervical epithelial abnormalities among adolescents within the past two decades.

Materials and Methods:

For this study, the reports of 156,342 cervical cytology were available of which 12,226 (7.8%) were from teenagers. A total of 192 teenagers with high grade intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) cervical cytology were identified. The ages ranged from 13 to 19 years with a mean of 17.7 years and a median of 18 years. Among them, 31.3% were pregnant, 12.0% were postpartum, and 13.5% were on oral contraceptive. Ninety-eight had prior cervical cytology.

Results:

The teenagers had statistically significant higher detection rates of overall abnormal cervical cytology (23.6% vs. 6.6%, P = 0), with 15.4% vs. 3.2% (P = 0) of low grade intraepithelial lesion (LSIL) and 1.8% vs. 1.0% (P = 2.56 × 10-13 ) of HSIL compared to women ≥20 years. The teenage group had the highest abnormal cytology among all age groups. The LSIL/HSIL ratio was 8.5:1 for teenagers and 3.1:1 for women ≥20 years. A total of 131 teenagers had cervical biopsies within 12 months of the HSIL cytology, with diagnoses of 39 CIN 3, 1 VAIN 3, 15 CIN 2, 62 CIN 1, and 14 had a negative histology (CIN 0). Only in 19 of these 39 women, the CIN 2/3 lesion proved to be persistent.

Conclusion:

We conclude that cytology screening of high risk teenagers is effective in detecting CIN 2/3 lesions. Moreover, treatment and careful follow-up can be realized.

Keywords

Adolescents

cervical cytology

HSIL

long-term outcomes

INTRODUCTION

The incidence and mortality of cervical cancer have decreased significantly in the past 30 years in the United States due to the widespread availability of cervical cytology screening, with the rates declining from 14.8 per 100,000 women in 1975 to 6.4 per 100,000 women in 2007.[1] When organized cervical cytology screening programs have been introduced into communities, marked reductions in cervical cancer incidence have followed.[23] However, cervical cancer still remains a significant health problem worldwide with an estimated 500,000 new cases and 240,000 associated deaths annually.[4] Approximately, 11,270 new cases of cervical cancer were diagnosed in the United States in 2009 with 4070 cervical cancer-related deaths.[5] In the European Union (EU) approximately 34,000 new cases and more than 16,000 cervical cancer-related deaths are reported annually.[6] It is estimated that 50% of women in whom cervical cancer is diagnosed each year have never had cervical cytology testing done, and another 10% have not been screened within the 5 years prior to diagnosis.[7] Therefore, any approach aiming to reduce the incidence and mortality due to cervical cancer would have to include increasing the coverage of unscreened or infrequently screened women. However, the concerns, with regards to adolescents and young women, have always been the risk of over screening and over treatment. The Council of EU recommended that cervical cytology screening should start between age 20 and 30 years, but preferentially not before age 25 or 30 years. The new 2009 guideline from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) stated that cervical cancer screening should begin at age 21 years regardless of the age of onset of sexual intercourse. This replaces the 2003 guideline, which states that cervical cytology screening should start approximately 3 years after initiation of sexual intercourse, but no later than age 21 years.[8] The new 2009 guideline is based on the high prevalence of HPV infection, high rate of regression of low grade intraepithelial lesion (LSIL), and very low incidence of cervical cancer in adolescents and young women, in addition to the anxiety, morbidity, expenses, and likely overuse of follow-up procedures.

However, many recent studies have shown a dramatic increase in the incidence of cervical epithelial abnormalities among adolescents in the past two decades with the rates of atypical squamous cell of undermined significance (ASC-US), LSIL, and high grade intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) ranging between 7–16%, 3–13%, and 0.2–3%, respectively.[9–16] Unlike LSIL cytology, there are only limited studies on the follow-up and outcomes of HSIL cytology in this population. This retrospective study documents the long-term follow-up findings in a cohort of teenagers (<20 years) with HSIL cervical cytology, over a 54-month period.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center (LSUHSC), Shreveport. All cases with HSIL cervical cytology diagnosed between January 2003 and December 2007 were electronically retrieved from the database of the Department of Pathology, LSUHSC. The demographic data and clinical information including the use of oral contraceptives, pregnancy, and postpartum history were extracted from the pathology reports. The base population in this study was mainly low-income underinsured women of mixed ethnicity, and the cervical cytology screening in this study was part of an organized screening program performed mainly in a Women Clinic at LSUHSC. Results of follow-up cervical biopsy, loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP), and repeat cervical cytology were collected until May 2010. Accessible records of cervical cytology test results prior to the HSIL cytology were also recorded. More than 99% of the cervical cytology specimens were processed using ThinPrep, liquid-based cytology. The corresponding cervical biopsies were defined as biopsies performed within 12 months from the dates of the HSIL cytology diagnosis, and biopsies performed after 12 months were considered as long-term follow-up. LEEP biopsies were similarly categorized. The long-term follow-up cervical cytology and histology was divided into four interval periods in months: 19–30, 31–42, 43–54, and >54 months. Statistical analysis was performed using the chi-square Fisher's exact t-test.

RESULTS

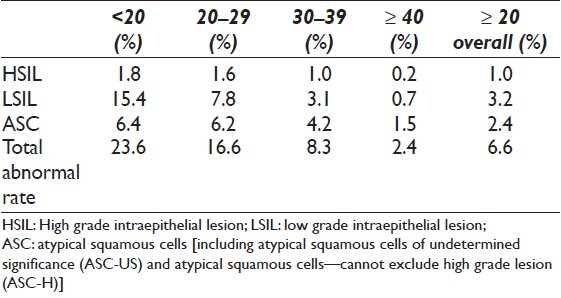

There were 156,342 cervical cytology tests performed and screened during the study period, which included 12,226 (7.8%) from teenagers and 144,116 (92.2%) from women ≥20 years. Table 1 shows the summary of cervical cytology diagnoses with age breakdown. Teenagers had statistically significant higher detection rates of overall abnormal cervical cytology (23.6% vs. 6.6%, P = 0), with 15.4% vs. 3.2% (P = 0) of LSIL and 1.8% vs. 1.0% (P = 2.56 × 10-13 ) of HSIL compared to women ≥20 years. The LSIL/HSIL ratio was 8.5:1 for teenagers and 3.1:1 for women ≥20 years. The teenage group had the highest abnormal cervical cytology, HSIL, LSIL and ASC among all age groups, followed with the 20-29 age group.

A total of 192 teenagers with HSIL cervical cytology were identified. The ages ranged from 13 to 19 years with a mean of 17.7 years and a median of 18 years. Among 31.3% of the women were pregnant, 12.0% were postpartum, and 13.5% were on oral contraceptive. Ninety-eight women had prior cervical cytology before January 2003, and 57 of them (57/98) had abnormal cytology, which included HSIL (10 cases), LSIL (26 cases), ASC-H (2 cases), and ASC-US (19 cases). Twenty-three teenagers also had prior cervical biopsies, including 6 CIN 2/3 and 17 CIN 1.

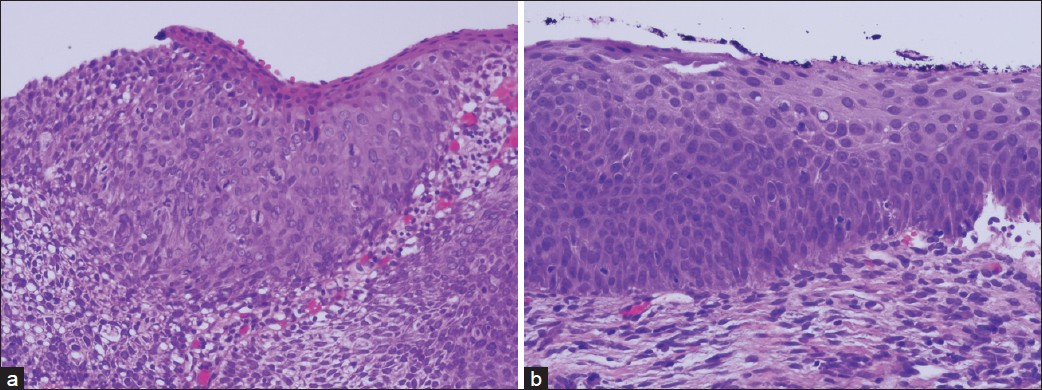

A total of 131 teenagers had follow-up cervical biopsies within 12 months. The histologic diagnoses were: 15 CIN 3, 1 VAIN 3, 39 CIN 2, and 62 CIN 1. The remaining 14 teenagers had a negative for dysplasia (CIN 0). Twenty-three teenagers had LEEP (17/23 within 12 months and 6/23 after 12 months). The diagnoses included 14 CIN 2/3, 1 endocervical glandular dysplasia, 5 CIN 1, and 3 CIN 0. Three teenagers had a second LEEP for recurrent HSIL. The youngest teenager with LEEP was 16 years with CIN 3 [Figure 1a] and positive margins. She had HSIL in follow-up cervical cytology and a second LEEP with CIN 2 [Figure 1b] at 15 months after the first LEEP.

- a) A 16-year-old girl had high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) on cervical cytology, and the cervical biopsy was severe squamous dysplasia (A, 200×, H and E), b) She underwent LEEP but with positive resection margins. She had two times HSIL cervical cytology during 15-month follow-up, and underwent for the second LEEP for moderate squamous dysplasia (B, 200×, H and E).

Table 2 shows the cytologic diagnoses in the 198 teenagers with long-term follow-up with 142 ending up with negative cytology. Table 3 shows the histologic diagnoses of 39 teenagers with histologic diagnosis with 19 CIN 2/3 cases.

DISCUSSION

Sexually active adolescent women are at a substantial risk for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, including high-grade lesions especially when there are associated high-risk factors. In this review of 12,226 cervical cytology smears from teenagers, the overall abnormal cervical cytology rate was 23.6% with HSIL, LSIL, and ASC rates of 1.8%, 15.4%, 6.4 %, respectively, which were significantly higher than that in women ≥20 years (6.6%, 1.0%, 3.2%, and 2.4%, respectively). These results are in accordance with previously published recent data.[10–16] It is significantly higher than the rate reported by Sadeghi et al. in 1984, who noted that the rate of abnormal cervical cytology among more than 190,000 adolescents aged 15–19 years was only 1.9%.[9] The reasons for these high rates of cervical epithelial abnormalities in teenagers are likely multifactorial, which probably includes high-risk sexual behaviors such as an early-onset of sexual intercourse and multiple sexual partners and HPV infection.[17–19] Recent studies confirmed the significant increased rates of CIN 2–3 and stage IA cancer in young patients.[2021] Study from Iceland showed the CIN3/AIS was significantly high in age 20–24 and 25–29, and the increased incidence of invasive carcinoma was mainly due to increased rates in the 25–34 year groups.[20]

The overuse of cervical cytology screening may be quite significant among young women, thereby putting enormous economic burden on the health care system. A recent study estimated that potentially unnecessary cervical cytology could approach 659,000 among 5.7 million women younger than 21 years, who are not sexually active.[22] This highlights the urgent need for the education of health care providers, to stress adherence to the guidelines, in order to reduce the economic burden and potentially unnecessary cervical screening cytology in young women. Overtreatment and the relative risk on future childbearing as well as the emotional impact of labeling an adolescent with a potential precancerous lesion are also significant, as adolescence is a time of heightened concern for self-image and emerging sexuality.[8] Arbyn et al. in a meta-analysis reported that LEEP had lower prenatal mortality, preterm delivery, and low birth weight compared to cold knife conization; however, LEEP was not completely free of adverse outcomes.[23] Significant increase in premature births in women previously treated with excisional procedures for dysplasia was also reported in a recent study by Kyrgiou et al.[24] Therefore, in teenagers the use of LEEP should be limited.

The regression rate of abnormal cytology in these young women should also be taken into account in planning treatment. Moscicki et al. demonstrated a regression rate of 61% and 91% for HPV/LSIL in adolescents after 1 and 3 years of follow-up, respectively, with only 3% progressing to CIN 3.[25] Two other studies in adolescents with biopsy confirmed CIN 2 showed 65% and 75% regression to negative after 18 months and 3 years, respectively.[1426] The regression rate was much higher in adolescents than that of adults from a meta-analysis study by Melnikow et al.[27] The update of ASCCP treatment guidelines for CIN 2/3 lesions in adolescents are observation-colposcopy and cytology or treatment using excision or ablation of the T-zone. However, it also stated “when CIN 2 is specified, observation is preferred. When CIN 3 is specified, or colposcopy is unsatisfactory, treatment is recommended”.[28] The reported high rates of regression support this guideline and immediate excision (“see and treat”) is not recommended for teenagers. From the literature, the treatment of CIN 2 lesions in adolescents is not consistent, so we recommend to carefully follow the ASCCP guidelines and limit LEEP to CIN 3 or persistent CIN 2 lesions.

We conclude that cytology screening of high-risk teenagers is effective in detecting CIN 2/3 lesions. Moreover, treatment and careful follow-up of these young women can be realized.

COMPETING INTEREST STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors of this article declare that we qualify for authorship as defined by ICMJE http://www.jcmje.org/#author. Each author has participated sufficiently in the work and takes public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content of this article.

SZ participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft and finish the manuscript, and performed the statistical analysis. JT participated in its design and writing the manuscript. Jthibodeaux participated in the data collection and helped to draft the manuscript. AB pariticipated in the data collection and helped to draft the manuscript. FA participated in its design and writing the manuscript.

Each author acknowledges that this final version was read and approved.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

This study was conducted with approval from Institutional Review Board of LSUHSC-Shreveport and was conducted only at LSUHSC-Shreveport. Authors take responsibility to maintain relevant documentation in this respect.

EDITORIAL / PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double blind model (authors are blinded for reviewers and reviewers are blinded for authors)through automatic online system.

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.cytojournal.com/text.asp?2011/8/1/9/81773

REFERENCES

- SEER cancer statistics review, 1975-2007. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute. 2010. Available at: http//seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2007

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of population screening for cancer of the uterine cervix in Nijmegen.The Netherlands. Prev Med. 1986;15:582-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures 2009.Atlanta (GA): ACS; 2010. Available at: http//www.cancer.org/downloads/STT/500809web.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- European guidelines for quality assurance in cervical cancer screening.Second edition-summary document. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:448-58.

- [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health. Cervical cancer. NIH Consensus Statement. 1996. 14:1-38. Available at: http//consensus.nih gov/1996/1996 cervicalCancer 102PDF.pdf.

- [Google Scholar]

- ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology, ACOG Practice Bulletin no. 109: Cervical cytology screening. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:1409-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in sexually active teenagers and young adults: Results of date analysis of mass Papanicolaou screening of 796,337 women in the United States in 1981. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1984;148:726-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cervicalvaginal smear abnormalities in sexually active adolescents: Implications for management. Acta Cytol. 2002;46:271-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- A study of 10,296 pediatric and adolescent Papanicolaou smear diagnoses in northern New England. Pediatrics. 1999;103:539-45.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cervical Papanicolaou smear abnormalities in inner city Bronx adolescents: Prevalence, progression and immune modifiers. Cancer. 1999;87:184-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cervical screening in under 25s: A high-risk young population. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2008;139:86-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adolescent cervical dysplasia: Histologic evaluation, treatment, and outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:141e1-e6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance in girls and women. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:632-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Intention to return for Papanicolaou smears in adolescents girls and young women. Pediatrics. 2001;108:333-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- High prevalence rate of human papillomavirus infection and association with abnormal Papanicolaou smears in sexually active adolescents. Am J Dis Child. 1989;143:1443-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- An update on human papillomavirus infection and Papanicolaou smears in adolescents. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2001;13:303-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- The natural history of human papillomavirus infection as measured by repeated DNA testing in adolescent and young women. J Pediatr. 1998;132:277-84.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cervical cancer: Cytological cervical screening in Iceland and implications of HPV vaccines. Cytopathology. 2010;21:213-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- The impact of cytological cervical screening and its changing role in the future. Cytopathology. 2010;21:355-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pap testing and sexual activity among young women in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:1213-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Perinatal mortality and other severe adverse pregnancy outcomes associated with treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: Meta-analysis. BMJ. 2008;337:a1284.

- [Google Scholar]

- Obstetric outcomes after conservative treatment for intraepithelial or early invasive cervical lesions: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2006;367:489-98.

- [Google Scholar]

- Regression of low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions in young women. Lancet. 2004;364:1678-83.

- [Google Scholar]

- Management of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2 in adolescent and young women. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2007;20:269-74.

- [Google Scholar]

- Natural history of cervical squamous intraepithelial lesions: A meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92:727-35.

- [Google Scholar]

- Update on ASCCP consensus guidelines for abnormal cervical screening tests and cervical histology. Am Fam Physician. 2009;80:147-55.

- [Google Scholar]