Translate this page into:

Hematolymphoid neoplasms in effusion cytology

*Corresponding author

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

Hematolymphoid neoplasms (HLNs) presenting as body cavity effusions are not a common finding. They may be the first manifestation of the disease. A diagnosis on effusion cytology may provide an early breakthrough for effective clinical management.

Aims:

Study the cytomorphology of HLNs in effusion cytology, determine common types, sites involved and uncover useful cytomorphologic clues to subclassify them.

Materials and Methods:

Twenty-four biopsy-proven HLN cases with malignant body cavity effusions and 8 cases suspicious for HLN on cytology but negative on biopsy are included in this study. Effusion cytology smears were reviewed for cytomorphological features: cellularity, cell size, nuclear features, accompanying cells, karyorrhexis, and mitoses.

Results:

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (37%) was the most common lymphoma type presenting as effusion followed by peripheral T-cell lymphoma (25%). Pleural effusion (75%) was most frequent presentation followed by peritoneal effusion (20.8%). Pericardial effusion was rare (4.1%). The common cytologic features of HLNs in effusions: high cellularity, lymphoid looking cells with nuclear enlargement, dyscohesive nature, and accompanying small lymphocytes. Mitosis and karyorrhexis were higher in high-grade HLNs when compared to low-grade HLNs. Myelomatous effusion showed plasmacytoid cells. Very large, blastoid looking cells with folded nuclei, high N: C ratio, and prominent nucleoli were seen in leukemic effusion.

Conclusion:

HLNs have characteristic cytomorphology and an attempt to subclassify them should be made on effusion cytology. Reactive lymphocyte-rich effusions cannot be distinguished from low-grade lymphomas based on cytomorphology alone. Ancillary tests such as immunocytochemistry, flow cytometry, and/or molecular techniques may prove more useful in this regard.

Keywords

Effusion cytology

leukemia

lymphocyte-rich effusion

lymphoma

INTRODUCTION

Hematolymphoid neoplasms (HLN) presenting as body cavity effusions is not a common finding. Very rarely, they can be thefirst sign of the disease.[1] In decreasing order of frequency, this is observed in non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), Hodgkin lymphoma, Leukemias, and rarely in other myeloproliferative or myelodysplastic syndromes. They are different from primary effusion lymphomas (PELs) which do not involve any other site.

Malignant effusions in HLNs may be the first manifestation or may occur during the disease course. Effusion cytology is an easily available, inexpensive diagnostic tool in this setting. Cytomorphological features can provide useful information regarding the nature of the disease. Cell size, mitosis, etc., being valuable morphologic clues.

Aims and objectives

(1) The aim of this study is to study the cytomorphology of HLNs in effusion cytology, (2) To determine the most frequently encountered HLNs in effusion fluids, (3) To assess the affinity of HLNs to any particular sites (pleura/peritoneum), and (4) To determine the feasibility of subclassification of HLNs on effusion cytology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is a retrospective study, wherein all cases of HLNs diagnosed on effusion cytology and with a biopsy confirmation during a 3-year period (June 2013– June 2016) are included in this study. The routine Pap-stained cytocentrifuge smears were reviewed for the following features: cellularity; cell size in comparison to that of small lymphocyte nucleus (SLN). They were categorized as small cell (1–1.5 times the SLN), large cell (2–2.5 times the SLN), and intermediate (between the two); nuclear features – chromatin, indentation, and nucleolus; cytoplasmic features – amount, granularity; background – small lymphocytes, mesothelial cells, tingible body macrophages. Other features were quantified as follows: karyorrhexis-minimal (+), moderate (++), abundant (+++), mitosis-rare (+), frequent (++), and brisk (+++).

Cell blocks were prepared from the residual fluid wherever available. The histomorphology on tissue biopsy and immunohistochemistry findings were studied in all cases.

RESULTS

A total of 32 cases were diagnosed as leukemia/lymphoma/suspicious for lymphoma on effusion cytology during this period. Of these 24 cases were confirmed to be malignant on histopathology and were included in this study. The remaining eight cases had a benign histopathology diagnosis and will be discussed separately.

Age ranged from 19 to 70 years with a mean age of 47 years. There were 14 males and 10 females with a male: female ratio of 1.4:1. Pleural effusion (19 cases) was the common presentation, followed by peritoneal (4), and pericardial effusion (1).

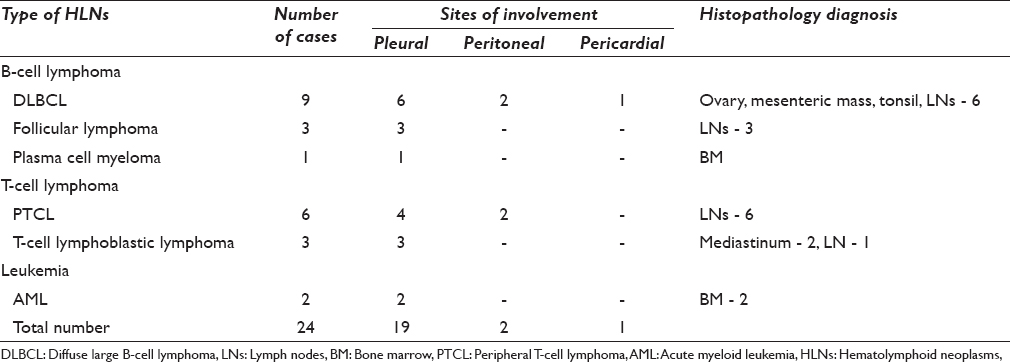

The various HLNs encountered in effusion cytology in this study are as depicted in Table 1.

The details of the cases which were misdiagnosed on effusion cytology are as shown in Table 2.

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

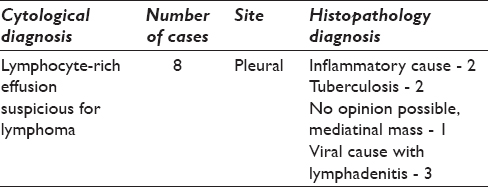

This was the most common lymphoma type presenting as effusion. The smears were cellular with >90% medium to large sized cells with large nucleus, coarse chromatin, one or more nucleoli, and moderate amount of cytoplasm [Figure 1a]. Brisk mitosis (+++) and prominent karyorrhexis (+++) were noted in all cases. Background occasional small lymphocytes were also noted.

- (a) Medium to large-sized lymphoid cells with nucleoli and brisk mitosis. Pap, ×200. Inset: Karyorrhexis, Pap, ×200. (b) Cell block showing small lymphoid cells with cleaved nuclei; admixed other cells seen. H and E, ×200. (c) Atypical plasmacytoid cells, binucleate cells, and mitosis. Pap, ×200. (d) Intermediate to large-sized “flower” cells (red arrow), Pap, ×400

Follicular lymphoma

Small-sized lymphoid cells with cleaved nuclei, scant cytoplasm, and admixed reactive mesothelial cells were observed. Mitosis was uncommon (+), and karyorrhexis was absent [Figure 1b].

Plasma cell myeloma

Sheets of plasmablasts and atypical plasma cells were noted. Frequent mitosis was noted (+++). Karyorrhexis was minimal (+) [Figure 1c].

Peripheral T-cell lymphoma

Intermediate sized cells with deeply indented nucleus. Occasional “flower cells” with multilobate nuclei, admixed mesothelial cells, rare mitosis (+), and minimal karyorrhexis (+) were seen [Figure 1d].

T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma

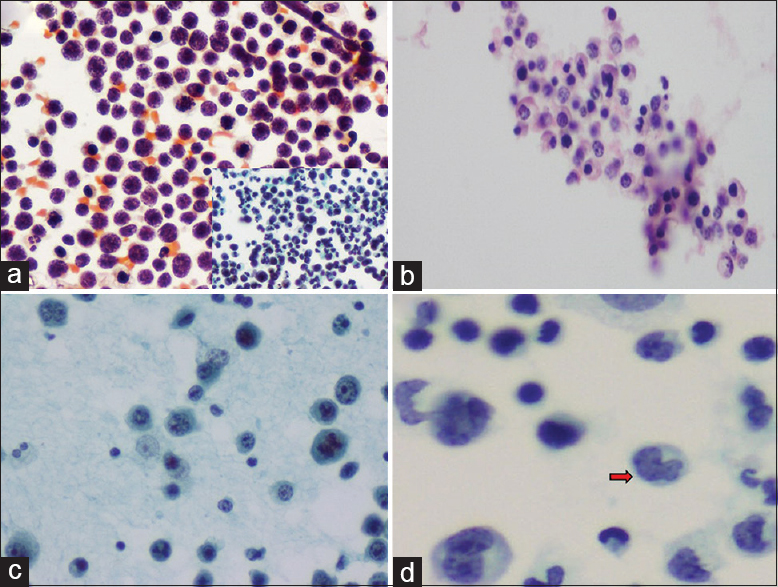

Cellular smears with >95% intermediate sized lymphoid cells with delicate nuclear membrane, granular chromatin, inconspicuous nucleoli, and scant cytoplasm were observed. Occasional “Hand mirror’ cells were also seen [Figure 2a]. Other cells were very rare. Mitosis (++) and moderate karyorrhexis (++) were seen.

- (a) Intermediate-sized lymphoid cells with delicate nuclear membrane, nuclear nicks (black arrow), and “hand mirror” cells (red arrow). Pap, ×200. (b) Very large cells, with a kidney-shaped, folded nucleus, fine chromatin, and single nucleolus. Pap, ×400. (c) Thick lymphocyte-rich smear, Pap, ×100. (d) Cellblock of a case of lymphocyte-rich effusion showing a polymorphous population of cells, H and E, ×200

Acute myeloid leukemia

Smears showed >95% very large cells (>5 times the SLN) with enlarged irregular to kidney-shaped to folded nucleus with fine chromatin, single prominent nucleolus, and moderate cytoplasm. Occasional small lymphocytes, karyorrhexis (+), and rare mitosis (+) were also seen [Figure 2b].

Lymphocyte-rich effusions misdiagnosed as suspicious for lymphoma

Cellular smears with reactive lymphocytes of near monomorphic sizes with an occasional mitosis was seen. No karyorrhexis was seen. Cellular crowding and thick smears were the contributing factors for misdiagnosis [Figure 2c and d].

DISCUSSION

Body cavity effusions may be the first presentation of HLNs or it may develop during the course of the disease (progression). However, PELs need to be ruled out. Pleural effusion as a complication of lymphomas has been reported in 20%–30% of cases.[23] However, involvement of peritoneal and pericardial cavities is uncommon. Even rarer is the occurrence of malignant effusion in patients with acute leukemia/myeloma.

The mechanism of pleural effusion in these patients can be explained as follows: (1) Pleural infiltration by the neoplastic cells, (2) Lymphatic obstruction, (3) Obstruction of thoracic duct.[4] Involvement of peritoneum/pericardium can also be explained along similar lines as follows: (1) Close proximity to the primary tumor, (2) Hematogenous dissemination, or (3) Widespread disease.

Malignancy in exudative effusions is more common than in transudative effusions (<8%). Other features such as elevated serum lactose dehydrogenase, serum protein levels, immunological defects, immature lymphocytes in peripheral blood, enlarged lymph nodes, hepatosplenomegaly are useful pointers to lymphomatous effusions.[5]

Cytomorphological study of the neoplastic lymphoid/myeloid cells has not been extensively described in the literature. Diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (DLBCLs) show intermediate to large sized cells with enlarged nuclei, 1 or more prominent nucleoli with frequent mitosis.[6] The authors observed prominent karyorrhexis and brisk mitoses in DLBCLs. Chen et al.[7] observed that patients with DLBCL with lymphomatous effusions have a poor prognosis and need aggressive treatment like Stage IV disease. They also recommended effusion cytology as an essential additional workup in these patients; 18% of their cases had lymphomatous effusion.

Chen et al.[8] opined that T-cell lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma should be deliberated in young patients with mediastinal mass with pleural effusion showing predominant small-to-medium-sized lymphoid cells with round-to-oval convoluted nuclei and fine chromatin with frequent mitosis and karyorrhexis. “Hand-mirror” cells have nuclear and cytoplasmic extensions involving one pole of the cell and had in the past been classically described in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. They have now also been observed in other lymphomas such as cutaneous natural killer cell lymphoma, Ki-1 lymphoma, Burkitt's lymphoma, B-Cell lymphomas with surface IgM-lambda, and with acute granulocytic/myelomonocytic leukemias.[9]

Peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL), NOS show monomorphic, intermediate-sized lymphoid cells with scant cytoplasm and irregular convoluted nuclear contours with some mimicking multilobate “flower cells.”[10] Follicular lymphoma (FL) in effusion cytology shows small-sized lymphoid cells with cleaved nuclei.[5] As was observed in our case, size is an important criteria to distinguish these two variants on morphologic grounds. In addition, accompanying cells– neutrophils, eosinophils are more common with PTCL than FL.

Acute and chronic leukemias rarely present as effusions. The presence of large-sized myeloblasts with enlarged indented nuclei, fine chromatin, 1 or more prominent nucleoli with moderate amount of lightly basophilic cytoplasm is a diagnostic pointer. These cells may be seen in clusters as well.[11]

Myeloma presenting as pleural/peritoneal effusion is extremely rare. The presence of atypical plasma cells with dense cytoplasm, inconspicuous perinuclear hof, eccentric pleomorphic nuclei with coarse chromatin, and prominent nucleoli are useful diagnostic features.[12] The authors also observed occasional binucleate cells.

Other subtypes of HLNs reported in literature include: Anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, with intermediate to large cells with irregular nuclei, RS-like cells, and cells with wreath-like arrangement of nuclei.[13] Marginal zone lymphoma (MZL) shows small- to intermediate-sized cells with round nuclei. Plasmacytoid differentiation and emperipolesis are peculiar features described in MZL.[1415]

Differential diagnosis includes reactive lymphocyte-rich effusions, other small round cell tumors, poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, and PEL. Reactive lymphocyte-rich effusions can be cellular and very difficult to differentiate from low-grade lymphoma on cytomorphology alone. Immunocytochemistry (ICC) or flow cytometry studies may be useful in this regard as benign lymphocyte-rich effusions consist predominantly of T-cells.[16] Other small round cell tumors such as small cell neuroendocrine tumors rarely involve peritoneal cavities. Poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma will show nuclear pleomorphism and at least focal acinar arrangement of cells. PEL is a rare type of NHL with involvement of serous cavities without lymphadenopathy. It affects immunosuppressed patients and human herpesvirus (HHV 8) is considered to be the etiological agent.[17] This lymphoma is associated with a very poor prognosis. In all cases in this study, there was either nodal or bone marrow involvement thus ruling out possibility of PEL. The cells are large (2–2.5 times the size of SLN), with high N: C ratio, round to convoluted nuclei, coarse chromatin, with amphophilic to basophilic cytoplasm (plasmablastic); binucleate and multilobate nuclei are also seen.[18]

Ancillary techniques such as – ICC, flow cytometry[1920] or molecular studies can be readily performed on effusion specimens to overcome these diagnostic challenges. Cell blocks are excellent choices for immunocytochemical evaluation of effusions. The various benefits of cell blocks include – better standardization, easy morphologic interpretation similar to tissue sections, multiple sections for immunomarkers, and easy archiving. The SCIP (substractive coordinate immunoreactivity pattern) approach recommends an immunopanel (vimentin, pancytokeratin, leukocyte common antigen, calretinin and Wilms tumor 1) which can eliminate mesothelial and other inflammatory cells to recognize a “second-foreign” population of tumor cells.[21] Furthermore, specific markers can be used subsequently.

CONCLUSION

Cytologic analysis of HLNs in effusion fluids can provide a rapid diagnosis and provide an early breakthrough in patient management. The presence of HLNs in effusions is not only associated with poor patient outcome but is also a predictor of disease relapse after chemotherapy and decreased survival. Cytomorphologic features of HLNs provide useful information regarding the nature of disease – large cells with frequent mitosis and karyorrhexis (DLBCL) associated with aggressive clinical coarse while small cells with cleaved nucleus and rare mitosis seen in indolent lymphomas (FL). Leukemias show very large cells with folded nuclei. Atypical plasmacytoid cells are a pointer to myeloma/plasmablastic lymphoma. Attempt should be made to subclassify HLNs on effusion cytology. Well-spread smears and study of cell blocks (with ICC) can prove useful in avoiding false positives.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The authors have no competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

Dr Vidya Monappa and Dr Saritha Reddy contributed in data collection, analyses and writing manuscript. Dr Ranjini Kudva edited the manuscript. All 3 authors were involved in conceptualizing the study.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

This is a retrospective morphological study not directly involving patients.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS (In alphabetic Order)

DLBCL - Diffuse large B cell lymphoma,

FL - Follicular lymphoma,

HHV8 - Human herpes virus 8,

HLN - Hematolymphoid neoplasm,

ICC - Immune cyto chemistry,

MZL - Marginal zone lymphoma,

NHL - Non Hodgkin lymphoma,

PEL - Primry effusion lymphoma,

PTCL - Peripheral T cell lymphoma,

SCIP - Substractive coordinate immunoreactivity pattern

SLN - Small lymphocyte nucleus.

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double-blind model (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

REFERENCES

- Cytopathologic Diagnosis of Serous Fluids. (1st ed). Philadelphia, USA: Elsevier, W. B. Saunders Company; 2007. p. :171-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pleural effusion in patients with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: A case-controlled study. Cancer. 1998;83:1607-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnostic pitfalls of discriminating lymphoma-associated effusions. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e800.

- [Google Scholar]

- Serous effusions in malignant lymphomas: A review. Diagn Cytopathol. 2006;34:335-47.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytological diagnosis of T lymphoblastic leukemia/Lymphoma in patients with pleural effusion as an initial clinical presentation: Two case reports of an algorithmic approach using complete immunohistochemical phenotyping. Acta Cytol. 2015;59:485-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder of hand-mirror cell morphology presenting in an eosinophilic loculated peritoneal effusion, with omental “caking”. Cytojournal. 2006;3:13.

- [Google Scholar]

- A case of peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified in a HCV and HTLV-II-positive patient, diagnosed by abdominal fluid cytology. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2016;7:S96-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytology and flow cytometry of malignant effusions of multiple myeloma. Diagn Cytopathol. 2000;22:147-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- CD-30(Ki-1)-positive anaplastic large cell lymphoma in a pleural effusion. A case report with diagnosis by cytomorphologic and immunocytochemical studies. Acta Cytol. 1999;43:498-502.

- [Google Scholar]

- A case of marginal zone lymphoma with extensive emperipolesis diagnosed on pleural effusion cytology with immunocytochemistry and flow cytometry. Cytopathology. 2016;27:70-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- A review of uncommon cytopathologic diagnoses of pleural effusions from a chest diseases center in Turkey. Cytojournal. 2011;8:13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary effusion lymphoma: An untrivial differential diagnosis for ascites. Yonsei Med J. 2009;50:862-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary effusion lymphoma: Cytopathologic diagnosis using in situ molecular genetic analysis for human herpesvirus 8. Mod Pathol. 2002;15:944-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Use of flow cytometry in the diagnosis of lymphoproliferative disorders in fluid specimens. Diagn Cytopathol. 2014;42:664-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- The flow cytometry, molecular analysis, and other special techniques. In: Shidham VB, Atkinson BF, eds. Cytopathologic Diagnosis of Serous Fluids (1st ed). Philadelphia, USA: Elsevier, W. B. Saunders Company; 2007. p. :195-205.

- [Google Scholar]

- Immunocytochemistry of effusion fluids: Introduction to the SCIP approach. In: Shidham VB, Atkinson BF, eds. Cytopathologic Diagnosis of Serous Fluids (1st ed). Philadelphia, USA: Elsevier, W. B. Saunders Company; 2007. p. :55-78.

- [Google Scholar]