Translate this page into:

Cytologic examination of ascitic fluid in a patient with pleural-based mass: A unique presentation of a rare tumor

*Corresponding author

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

A 47-year-female presented with complaints of cough, hemoptysis, and loss of weight for 1 month. Axial contrast-enhanced computed tomography showed moderately enhancing homogeneous left pleural mass, with associated mild pleural effusion. Pleural fluid cytology was followed by pleural biopsy. After 2 months, she had new complaints of pain and swelling of abdomen. Imaging studies revealed only ascites. Ascitic fluid was sent for cytological examination. The fluid was slightly viscous and hemorrhagic.

QUESTION

What is your interpretation of cytology of ascitic fluid?

-

Metastatic adenocarcinoma

-

Reactive mesothelial proliferation

-

Malignant mesothelioma

-

Papillary mesothelial hyperplasia

ANSWER

The correct cytopathologic interpretation is:

C. Malignant mesothelioma

The cytopathologic diagnosis of malignant mesothelioma has always been challenging owing to the overlapping morphologic features with its other differential diagnoses. However, careful attention to the cytologic details combined with immunohistochemical staining on cell block can be of immense value in situations where cytological analysis of fluid may be the only available option.

In the present case, the cytologic features of malignant mesothelioma which overlapped with its closest differential diagnosis of metastatic adenocarcinoma were as follows:

-

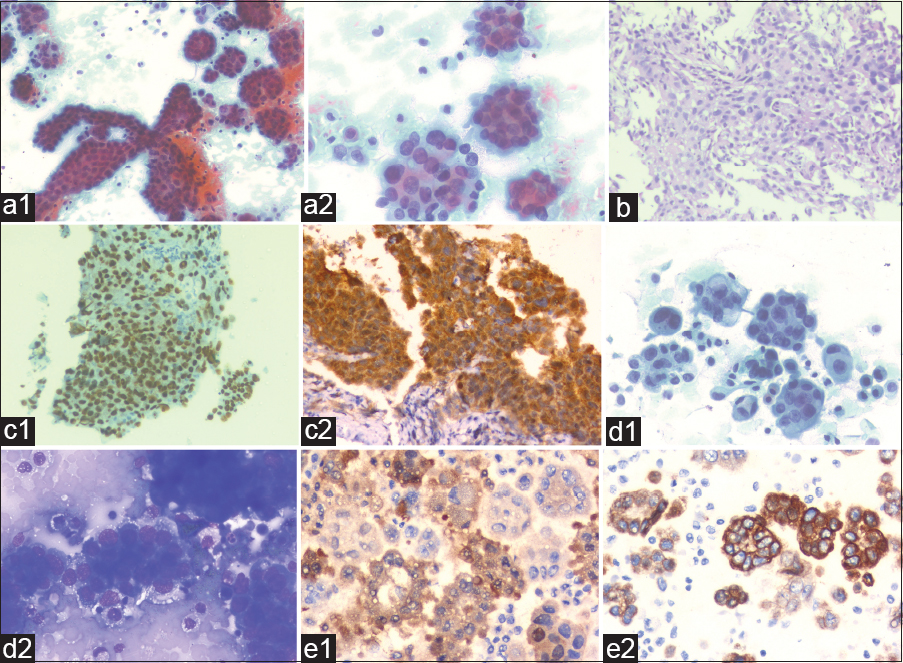

Arrangement of cells in tubulopapillary and acinar pattern [Figure 1a1 and a2]

-

Nuclear hyperchromasia

-

Presence of peripherally arranged large vacuoles.[Figure 1d2].

The cytomorphologic features (in the present case) which generally favor a malignant mesothelioma over metastatic adenocarcinoma are as follows:

- (a1 and a2) The pleural fluid smears were very cellular comprising of three-dimensional papillaroid and tubular clusters of malignant cells. The tumor cells showed moderate pleomorphism, clumped chromatin, and prominent nucleoli. In addition, numerous mitotic figures were also noted (Papanicolaou stain). (b) Pleural biopsy showed pleomorphic tumor cells arranged in tubulopapillary and glandular pattern along with fibrocollagenous tissue (hematoxylin and eosin stain). (c1 and c2) Immunohistochemistry showed nuclear positivity for WT1 and nuclear and cytoplasmic staining for Calretinin. (d1) Ascitic fluid smears were highly cellular with formation of cell balls having knobby contours. In higher magnification, features such as cell-in-cell engulfment, giant atypical mesothelial cells were seen. (Papanicolaou stain). (d2) Irregularly distributed variable sized cytoplasmic vacuoles were also seen (May Grunwald Giemsa stain). (e1 and e2) Immunohistochemical stain done on cell block from ascitic fluid sample showing positive staining for calretinin and CK5/6

-

Presence of large cell balls with knobby or berry-like contours containing nuclei overlapping with each other

-

Presence of giant mesothelial cells [Figure 1d1]

-

Presence of cell-in-cell engulfment [Figure 1d1].

The reactive mesothelial proliferations form smaller, uniform, less complex groups compared to malignant mesothelial proliferations.

FURTHER WORK UP

The tumor cells were also positive for WT1, Calretinin [Figure 1c1 and c2] p53 and Cytokeratin 5/6 and stained negatively for PAX 8, BerEP4, Desmin, CEA, and TTF 1. With the biopsy diagnosis of malignant mesothelioma [Figure 1b], neoadjuvant chemotherapy was planned for the patient. Other metastatic work-ups (including bone scan) were negative. There was no lymphadenopathy. Post three cycles of chemotherapy, pleurectomy, and decortication were done. The pleurectomy specimen comprised of multiple small bits and flap-like grayish brown tissue. The histopathological sections showed residual tumor cells (around 40%) with similar morphology as seen in the small biopsy along with areas of necrosis (post-neoadjuvant chemotherapy-induced changes). The patient was discharged after postoperative care, and she improved symptomatically over a period of 2 months. However, this improvement in symptoms was interrupted by new complaints of pain, discomfort, and swelling in the abdomen. On clinical evaluation, there was ascites which was tapped and sent for cytological examination. There was no evidence of any detectable mass lesion in ultrasonographic (USG) studies of abdomen and pelvis. With similar morphologic and immunohistochemical profile (which was performed on cell block [Figure 1e1 and e2]) came a diagnosis of malignant mesothelioma involving both pleural and peritoneal cavities. No further radiological workup (other than USG) was possible as the patient did not survive for long after the presentation with ascites. The patient was a homemaker and did not have any history of exposure to asbestos in her life which is also an odd finding in our case.

ADDITIONAL QUIZ QUESTIONS

-

Which virus has been implicated in the pathogenesis of malignant mesotheliomas?

-

HTLV

-

HPV

-

SV40

-

EBV.

-

-

Which histologic subtype of mesothelioma is supposed to have grave prognosis?

-

Epithelioid

-

Sarcomatoid

-

Mixed.

-

-

Which subtype of asbestos fiber has the maximum propensity to cause mesothelioma?

-

Serpentine

-

Crocidolite

-

Chrysotile

-

Amosite.

-

ANSWERS TO ADDITIONAL QUIZ QUESTIONS

-

SV40 is an oncogenic DNA virus. It induces DNA strand breaks in human mesothelial cells. The viral large T-antigen (Tag) inactivates the function of the tumor suppressor genes p53 and RB and induces chromosomal aberrations. The small t-antigen (tag) may contribute to transformation by binding to the protein phosphatase PP2A. The viral genomic sequences have been frequently detected in mesotheliomas, bone sarcomas, brain tumors, and few Non-Hodgkin's lymphomas

-

Sarcomatoid pattern of mesothelioma is listed in the adverse prognostic factors of malignant mesothelioma

-

Amphibole asbestos has the maximum propensity to cause mesotheliomas. There are two distinct subtypes, namely amosite and crocidolite. Crocidolite is more potent than amosite (5:1) in this association.

BRIEF REVIEW OF THE TOPIC

Malignant mesotheliomas are rare tumors accounting for <1% of all cancer deaths in the world.[1] Mesothelioma involving the serosal sacs is known however mesothelioma involving more than one serosal cavity has rarely been reported.[2] The present case is an extremely rare report of pleural and peritoneal malignant mesothelioma which could be synchronous primary or metastatic.

Historically known to be a tumor induced by exposure to asbestos, the peak age of incidence is sixth to seventh decade;[3] however, our patient did not have any such history. The International Mesothelioma Interest Group panel recommends that a cytologic suspicion of malignant mesothelioma should be followed by biopsy confirmation that must be supported by appropriate clinical and radiologic findings.[4] There are many histopathological subtypes of mesothelioma such as the epithelioid (tubulopapillary, micropapillary trabecular, acinar, solid, clear cell, signet ring cell, small cell, rhabdoid, and pleomorphic), sarcomatoid or biphasic. Depending on the histological subtype, the cytology of the mesothelioma may be varied ranging from bland to very pleomorphic tumor cells.[4] Our case is the tubulopapillary subtype which closely mimics lung adenocarcinoma morphologically. In the pleural cavity, it has to be differentiated from involvement by lung adenocarcinoma which is the most common cause of pleural infiltration/mass with effusion. The epithelial cells can be differentiated from mesothelioma cells with the help of immunohistochemical markers (EMA, CEA-monoclonal, Ber-EP4, TTF1, Napsin A for epithelial origin while calretinin, CK 5/6, WT1, and D2-40 for mesothelial origin). Although EMA staining can be seen in both adenocarcinomas and mesotheliomas, the pattern of staining is different. While it is membranous in epithelial cells, the staining is cytoplasmic in mesothelioma. Morphologically high cellularity, large cell balls (50 cells) with berry-like pattern, complex papillary pattern with cellular stratification, cytologic atypia, very prominent nucleoli, and frequent mitotic figures including atypical ones differentiates mesothelioma from reactive mesothelial cells.[4] Other features such as intercellular windows, with lighter dense cytoplasm edges, and low nuclear to cytoplasmic ratios with the presence of macronucleoli are also mentioned.[5] However, these features have considerable overlap with reactive mesothelial cells. Hence, histopathology is a compulsory requisite for the definite diagnosis along with a panel of immunohistochemical markers.[6] Recent diagnostic markers such as a combination of BAP1 (BRCA-associated protein) immunohistochemistry and p16 FISH have been advocated by some authors. According to a study by Hida et al. the detection of loss of nuclear staining of BAP1 by IHC combined with the homozygous deletion of p16 detected by in situ hybridization offer a high sensitivity of 92.5% in the differentiation of benign versus malignant mesothelial cell proliferations.[7]

The cytomorphological diagnosis has been stressed on by some authors[8] considering the fact that cytological samples may be the only available material for the diagnostic workup. Furthermore, the situation is extremely critical in cases of peritoneal mesothelioma in women[9] as they have radiologic as well as pathological features mimicking advanced serous adenocarcinomas of abdomen. Peritoneal adenocarcinomas are immunohistochemically positive for panCk and negative for calretinin while both being positive for WT1.[4] There are reports of synchronous occurrence of mesotheliomas with other adenocarcinomas,[1011] but literature review reveals only an occasional report of this tumor involving both pleural and peritoneal cavities.[2]

SUMMARY

Body fluids may be the only available sample for diagnosis of tumors affecting the serous cavities. Hence, detailed cytologic examination carries utmost importance in spite of morphologic overlaps.

Peritoneal mesotheliomas need to be distinguished from advanced intra-abdominal serous adenocarcinomas especially in women with the help of immunohistochemical stains pancytokeratin and calretinin.

Dual site mesothelioma is a rare possibility which may be encountered.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors of this article declare that we qualify for authorship as defined by ICMJE.

Each author has participated sufficiently in work and takes public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content of this article.

PD has contributed in the interpretation of the case findings and drafting of the manuscript.

DG has contributed in the interpretation of the case findings, drafting of the manuscript, and interdepartmental coordination.

VR has been involved in design and coordination.

PS has contributed in clinical detailing of the case and drafting of the manuscript.

NS has contributed in interpretation of case findings and drafting of the manuscript.

RG has contributed the radiological details and has been involved in drafting of the manuscript.

Each author acknowledges that this final version was read and approved.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

As this is a quiz case without identifiers, our institution does not require approval from Institutional Review Board (or its equivalent).

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS (In alphabetic order)

-

BAP 1- BRCA-associated protein 1

-

CECT - contrast-enhanced computed tomography

-

Pan CK - Pancytokeratin

-

SV 40 – Simian virus 40

-

USG - Ultrasonography.

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double-blind model (the authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to acknowledge the Department of Medicine and Radiology for their contribution in the diagnosis of this case.

REFERENCES

- Neoplasms of the pleura. In: Dail and Hammar's Pulmonary Pathology. Neoplastic Diseases of Lung. Vol 2. New York: Springer; 2008. p. :558-600.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synchronous pleural and peritoneal malignant mesothelioma: A case report and review of literature. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:2484-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tumours of the pleura: Mesothelial tumours. In: Travis WD, Brambilla E, Müller-Hermelink K, Harris CC, eds. Pathology and Genetics: Tumours of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus and Heart. Lyon: IARC Press, International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2004. p. :128-36.

- [Google Scholar]

- Guidelines for pathologic diagnosis of malignant mesothelioma: 2012 update of the consensus statement from the international mesothelioma interest group. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:647-67.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diffuse malignant mesothelioma of the peritoneum and pleura, analysis of markers. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:476-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- BAP1 immunohistochemistry and p16 FISH results in combination provide higher confidence in malignant pleural mesothelioma diagnosis: ROC analysis of the two tests. Pathol Int. 2016;66:563-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- The diagnostic and molecular characteristics of malignant mesothelioma and ovarian/peritoneal serous carcinoma. Cytopathology. 2011;22:5-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Malignant peritoneal mesothelioma in women: A study of 75 cases with emphasis on their morphologic spectrum and differential diagnosis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2005;123:724-37.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synchronous diffuse malignant mesothelioma and carcinomas in asbestos-exposed individuals. Histopathology. 2003;43:387-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- Malignant mesothelioma of the pleura and other malignancies in the same patient. Tumori. 2007;93:19-22.

- [Google Scholar]