Translate this page into:

Diagnosis of atypia/follicular lesion of undetermined significance: An institutional experience

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

The overall malignancy rate for the thyroid fine-needle aspiration (FNA) diagnosed as atypia of undetermined significance/follicular lesion of undetermined significance (AUS/FLUS) ranges from 5% to 30%. In this study, we present our institutional experience with thyroid nodules diagnosed as AUS/FLUS and further stratified into subcategories. In addition, we also assessed the significance of various clinicopathologic factors that may influence AUS/FLUS diagnoses and their outcomes.

Design:

A search of our laboratory information system was performed to identify all in-house thyroid FNA cases diagnosed as AUS/FLUS from 2008 to 2012. The data were collected and characterized by patient demographic information, cytopathology diagnosis with sub-classifiers and follow-up.

Results:

The case cohort included 457 cases diagnosed as AUS/FLUS. These were further sub-classified into one of six subcategories depending on the cytomorphologic findings and suspicion for or against a neoplastic process. Of the 457 cases, repeat FNA and/or surgical follow-up was available in 363 cases. There were 182 (39.8%) cases with cytologic follow-up only; 18 (9.9%) remained as AUS/FLUS, while 158 (86.8%) were re-classified with the majority being benign (142 cases). Histologic follow-up was available in 181 (39.6%) cases. There were 60 malignant cases confirmed by surgical excision, with an overall malignancy rate of 33.1%. The malignancy rate was 38.8% for cases with a repeat FNA versus 25.6% for cases that went directly to surgery without a repeat FNA. Papillary thyroid carcinoma accounted for 93.3% (56 cases) of the malignant cases.

Conclusion:

Based on our study, even though the malignancy rate of AUS/FLUS cases is similar to those reported for cases diagnosed as follicular neoplasm/suspicious for follicular neoplasm, we are of the belief that these comparable malignancy rates are a product of better clinical management and selection of patients diagnosed as AUS/FLUS for surgery after a repeat FNA.

Keywords

Atypia of undetermined significance

Bethesda system for reporting thyroid cytopathology

fine-needle aspiration

follicular lesion of undetermined significance

thyroid

INTRODUCTION

Atypia of undetermined significance/follicular lesion of undetermined significance (AUS/FLUS) is a heterogeneous diagnostic category of the Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology (TBSRTC). It is comprised of cases that cannot be definitively diagnosed as benign, suspicious for/consistent with neoplasm, suspicious for malignancy or malignant.[1] There are various interpretive scenarios depicted and illustrated in TBSRTC that may warrant a diagnosis of AUS/FLUS. These include specimens that may show focal architectural or nuclear atypia whose significance cannot be further determined (microfollicle or papillary formation, predominance of oncocytic follicular cells, rare cells with atypical nuclear features of papillary thyroid cancer, focal nuclear atypia in follicular and lymphoid infiltrates) and cellular aspirates that are limited by obscuring blood or poor fixation. Since these aforementioned features are entirely based on the observer, there exists a low inter-observer agreement and poor reproducibility for cases diagnosed as AUS/FLUS.[2] The recommended management for nodules with an initial AUS/FLUS diagnosis is clinical correlation and repeat fine-needle aspiration (FNA) at an appropriate interval.[1] In the post-Bethesda thyroid FNA classification era, the risk of malignancy has been reported to a range between 5% and 15% in patients with a diagnosis of AUS/FLUS.

In our previous review of thyroid cytopathology reporting schemes, a number of studies reported a higher risk of malignancy for thyroid FNA specimens diagnosed as indeterminate beyond the rates recommended by TBSRTC.[3] In the study by Jo et al., a majority of initial AUS/FLUS cases received follow-up surgery rather than the recommended repeat FNA.[4] Renshaw, in concordance with other studies, noted that thyroid FNA cases subcategorized as AUS/FLUS – not otherwise specified and AUS/FLUS - rule out follicular neoplasm had a similar malignancy rate to cases diagnosed as follicular neoplasm (FN)/suspicious for follicular neoplasm (SFN).[567] Therefore, even though these two AUS/FLUS subgroups may theoretically have similar malignancy rates to FN/SFN, the case management may entirely be dictated by which TBSRTC category they are placed into (repeat FNA for AUS/FLUS vs. surgical excision for FN/SFN). Some authors have suggested sub-classifiers to further stratify AUS/FLUS cases.[89101112] These studies have shown that even though the overall risk of malignancy is relatively low, sub-classifying AUS/FLUS with focal abnormal cytomorphological features may help in better management of patients.

In this study, we present our institutional experience with thyroid nodules diagnosed as AUS/FLUS and further stratified into subcategories. In addition, we also assessed the significance of various clinicopathologic factors that may influence AUS/FLUS diagnosis and their outcomes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A retrospective search of our laboratory information system was performed to identify all in-house thyroid FNA cases that were performed under ultrasound guidance and diagnosed as AUS/FLUS from 2008 to 2012. All thyroid FNAs were aspirated by a team of endocrinologists or radiologists using a 25-27 gauge needle; generally with 2–3 passes. A portion of each pass was used to make an air-dried slide, an alcohol fixed slide, with the remaining specimen in the needle hub rinsed in PreservCyt solution (Hologic, Marlborough, MA, USA) to prepare a ThinPrep slide (Hologic). A rapid on-site evaluation (ROSE) by staff cytopathologists was performed in nearly all in-house thyroid FNAs.

All cases were reported by one of five staff cytopathologist using TBSRTC. AUS/FLUS cases were further sub-classified into one of the following subcategories (SC): SC1 - favor benign, however, a FN could not be excluded due to increased cellularity; SC2 - specimens with focal nuclear overlapping and crowding; SC3 - scant specimens with focal nuclear overlapping and crowding; SC4 - specimens with focal nuclear overlapping and crowding in a background of lymphocytic thyroiditis; SC5 - few cells with features suspicious for papillary thyroid cancer (PTC); and SC6 - specimens in which FN cannot be excluded (with miscellaneous morphologic classifiers).

Data points collected for this study included: Patient demographics, size of the thyroid nodule sampled, aspirator, pathologist rendering the final diagnosis, and applicable follow-up. The data were collected and characterized by patient demographic information, cytopathology diagnosis with sub-classifiers and follow-up. Only cases that were diagnosed as AUS/FLUS were included in the study, however, patients younger than 18 years, nodules aspirated without ultrasound guidance and cases sent to our institution for a second opinion were excluded. The applicable surgical pathology follow-up was matched to the size and location of the index nodule. Data processing was performed by employing the Microsoft Excel software (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA).

RESULTS

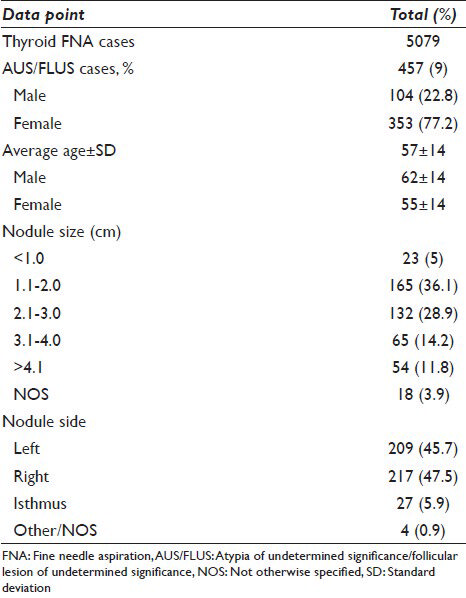

The characteristics of the case cohort is illustrated in Table 1 and included 5079 thyroid FNAs performed over the course of the 5-year study period (2008-2012); of these, 457 (9%) cases were diagnosed as AUS/FLUS. The mean age of the patients was 57 years at diagnosis with 353 (77%) females and 104 (23%) males. There was a slight increase in the age at diagnosis of AUS/FLUS for males (62 years vs. 55 years for females); 209 (45.7%) nodules occurred in the left and 217 (47.5%) in the right lobe. The size of the aspirated nodule was available in 439 of 457 (96.1%) cases; the average size was 2.54 cm with a slightly larger average size for males (2.72 cm vs. 2.48 cm for females). Twenty-three (5%) nodules measured <1.0 cm, 297 (65%) between 1.1 and 3.0 cm and 119 (26%) >3.1 cm.

All thyroid FNAs were performed under ultrasound guidance; 237 (51.9%) nodules were aspirated by a team of endocrinologists and 220 (48.1%) by a team of radiologists. The average nodule size was 2.42 cm for those aspirated by endocrinologists and 2.67 cm aspirated by radiologists. Nodules measuring <1.0-3.0 cm were more frequently aspirated by an endocrinologist than a radiologist (178 [55.6%] vs. 142 [44.4%]); whereas, nodules over 3.1 cm were more frequently aspirated by a radiologist than an endocrinologist (62 [53%] vs. 55 [47%]).

Atypia of undetermined significance/follicular lesion of undetermined significance diagnosis and sub-classification

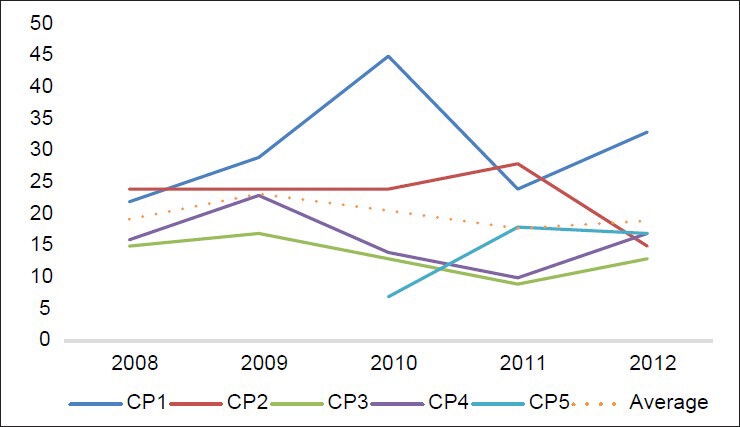

The utilization of AUS/FLUS over the course of the 5 years ranged from 77 cases to 103 cases/year by five cytopathologists [Figure 1]. The ratio of AUS/FLUS to all thyroid FNA diagnoses ranged from 8.1% to 10.8%. There was substantial variation in the utilization of AUS/FLUS among the five cytopathologists (CP) [Figure 2]. Of 457 cases diagnosed as AUS/FLUS, 268 (58.6%) were interpreted by two (CP1: 153 [33.5%] and CP2: 115 [25.2%]) and the remaining 189 (41.4%) by three cytopathologists (CP3: 67 [14.7%], CP4: 80 [17.5%], and CP5: 42 [9.2%]). All AUS/FLUS cases were further sub-classified into one of the aforementioned subcategories (SC1-SC6) at the time of the diagnosis [Table 2]. Of the 457 cases, 16 (3.5%) were sub-classified as SC1, 187 (40.9%) as SC2, 157 (34.5%) as SC3, 64 (14%) as SC4, 22 (4.8%) as SC5, and 11 (2.4%) as SC6. The average nodule size was 2.43, 2.41, 2.79, 2.23, 2.72, and 2.75 cm for SC1-SC6, respectively. The average age for cases sub-classified as SC1-SC6 was: 48, 57, 59, 55, 48, and 58 years, respectively.

- Overall number of atypia of undetermined significance/follicular lesion of undetermined significance (AUS/FLUS) cases by year

- Number of atypia of undetermined significance/follicular lesion of undetermined significance cases by cytopathologist/year. CP = Cytopathologist

Surgical and repeat fine-needle aspiration follow-up

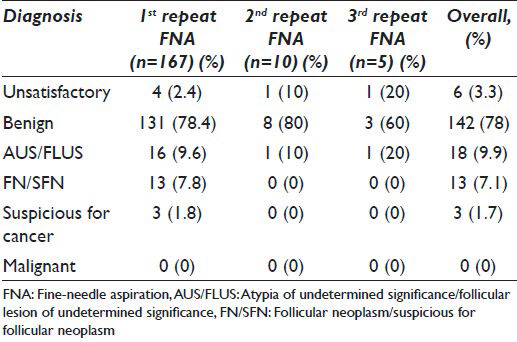

Of the 457 AUS/FLUS cases, repeat FNA and/or surgical follow-up was available in 363 (79.4%) cases [Table 2]. A repeat FNA was performed in 285 of 457 cases; 215 (75.4%) were performed by an endocrinologist and 70 (24.6%) by a radiologist. Most cases had one repeat FNA (266 cases [93.3%]); multiple repeat FNAs were performed in only 19 (6.7%) cases. The majority of repeat FNAs (76.5%, 218 cases) were performed in AUS/FLUS cases sub-classified as SC2 and SC3.

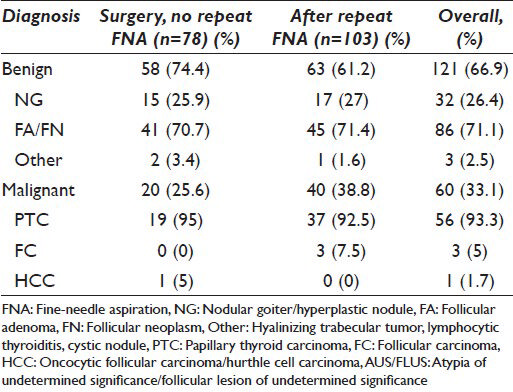

There were 182 (39.8%) cases with cytologic follow-up only; 167 (91.8%) received one repeat FNA, 10 (5.5%) received two and 5 (2.7%) with three [Table 3]. Overall, 18 (9.9%) remained as AUS/FLUS, while 158 (86.8%) were re-classified with the majority being benign (142 cases) and 6 (3.3%) were unsatisfactory. Histologic follow-up was available in 181 (39.6%) cases; 78 (43.1%) after the initial AUS/FLUS diagnosis, 99 (54.7%) after the first repeat FNA and 4 (2.2%) after the second repeat FNA [Table 4]. Of the 78 cases that went directly to surgery, 58 (74.4%) were benign (15 hyperplastic/goiter, 41 follicular adenoma/FN, 1 lymphocytic thyroiditis and 1 hyalinizing trabecular tumor) and 20 (25.6%) were malignant (19 papillary thyroid carcinomas and 1 oncocytic follicular carcinoma/Hurthle cell carcinoma). Of the 103 cases that received one or two follow-up repeat FNAs, 63 (61.2%) were diagnosed as benign (45 follicular adenoma/FN, 17 hyperplastic/goiter, and 1 cystic nodule) and 40 (38.8%) as malignant (37 papillary thyroid carcinomas and 3 follicular carcinoma) on histologic follow-up.

There were 60 malignant cases confirmed by surgical excision for an overall malignancy rate of 33.1% [Table 5]. The malignancy rates for each AUS/FLUS subcategory (SC) were: SC1-25%, SC2-32%, SC3-25%, SC4-54%, SC5-50%, and SC6-17%. The size of the malignant nodule ranged from <1.0 cm to >4.1 cm; 5 (8.3%) nodules measured <1.0 cm, 20 (33.3%) between 1.1 and 2.0 cm, 17 (28.3%) between 2.1 and 3.0 cm, 10 (16.7%) between 3.1 and 4.0 cm and 8 (13.3%) >4.1 cm. The malignancy rate for AUS/FLUS cases undergoing repeat FNA was 38.8%. Almost half of the malignant cases were initially interpreted as AUS/FLUS by one cytopathologist, CP1: 25 cases (41.7%); followed by CP2: 13 cases (21.7%), CP4: 12 cases (20%), CP3: 5 cases (8.3%), and CP5: 5 cases (8.3%).

Papillary thyroid carcinoma accounted for 93.3% (56 cases) of the malignant cases with 81.7% (49 cases) characterized as the follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma. There were three cases of follicular carcinoma and one case of oncocytic follicular/Hurthle cell carcinoma. Of the 121 benign cases, 71.1% (86 cases) were follicular adenomas/FNs, 26.4% (32 cases) were nodular goiter/hyperplastic nodules and 2.5% (3 cases) were other benign/neoplastic nodules (hyalinizing trabecular tumor, lymphocytic thyroiditis and benign cystic nodule). Incidental microcarcinoma was identified in 79 (43.6%) cases, the majority (60.8%, 48 cases) occurring in cases with benign index nodules.

DISCUSSION

The Bethesda thyroid FNA classification was developed with intent to provide a reporting system for thyroid FNA results that was uniform between laboratories and effectively corresponded cytologic interpretations for proper patient follow-up and management. The AUS/FLUS category of this scheme was intended to categorize the subset of cases that could not be definitively classified as benign, suspicious or malignant. It was well understood that this category would represent a heterogeneous set of cases with anticipated usage of 3-6% and overall risk of malignancy of 5-15%.[1] As more laboratories adopted TBSRTC and shared their experiences, variable usage and malignancy rates surpassing TBSRTC guidelines have been reported in the literature.

In the current study, there was a steady increase in the number of thyroid FNA cases (950-1174 cases) over the 5-year study period (2008-2012), yet the usage of AUS/FLUS remained steady with an average of 91 cases/year. At our institution, AUS/FLUS cases were further sub-classified based on the cytomorphologic findings and suspicion for or against a neoplastic process. The surgical pathology follow-up showed different malignant outcomes for each of the subcategories. The highest malignancy rates (53.8% and 50%) were encountered in AUS/FLUS cases in which sub-classifier notes “focal nuclear overlapping and crowding in a background of chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis” and “few cells with nuclear features suspicious for papillary thyroid carcinoma” were utilized (SC4 and SC5). Our findings are similar to what has been reported by other authors. A study by VanderLaan et al. reported a malignancy rate close to 30% in a subset of cases which exhibit cytomorphologic features suggestive but not diagnostic of papillary thyroid carcinoma as compared to 16% in cases with only architectural atypia.[10] A similar study by Renshaw, which pre-dated TBSRTC, also found that cases diagnosed as “atypical, rule out papillary carcinoma” had a 38% malignant rate versus 22% for cases diagnosed as “atypical, rule out FN”.[5]

Interestingly, a high rate of malignancy (53.8%) was also noted in AUS/FLUS cases with focal nuclear overlapping and crowding in a background of chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis (SC4). It is well-known that chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis may obscure subtle features of PTC (peri-nuclear halos, nuclear grooves, nuclear enlargement and crowding). On the other hand, it is also a common practice not to render a “suspicion of papillary carcinoma” diagnosis based on subtle nuclear atypia such as nuclear chromatin clearing in FNA specimens with chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis to avoid over diagnosis of reactive changes.[131415] In 344 (75.3%) cases, the sub-classifier note “focal nuclear overlapping and crowding” was utilized based on adequate (SC2) or limited cellularity (SC3) with malignancy rates of 32.3% and 25%, respectively. Together, these are higher than those reported in the literature for AUS/FLUS cases with architectural atypia.[101617] Our findings are in agreement with other studies that conclude sub-classifying AUS/FLUS can impact patient follow-up regimens and provide guidance toward a repeat FNA or surgery, especially in multi-disciplinary clinical settings.[18]

According to TBSRTC, the recommended management for thyroid nodules with an initial AUS/FLUS diagnosis is clinical correlation and repeat FNA.[1] This is in contrast to guidelines from the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/Associazione Medici Endocrinologi/European Thyroid Association Task Force which favors surgery over observation and repeat FNA.[19] It has been shown by many studies that a definite diagnosis can be rendered in more than half of cases diagnosed as “atypical” on repeat FNA, allowing for better selection of patients for surgery.[2021] Recent studies have reported variable rates for repeat FNA ranging from 7.9% to 46.4% in AUS/FLUS cases.[42223242526] In our study, 285 cases (62.4%) of AUS/FLUS cases underwent repeat FNA; 182 cases received repeat FNA with no further surgical follow-up. A definitive diagnosis was rendered in 158 (86.8%) cases; the majority (142 cases) was benign, 13 were FN/SFN and 3 were suspicious for malignancy. There were 18 cases that remained as AUS/FLUS after the first repeat FNA and 6 were unsatisfactory. Surgery is indicated for cases with successive AUS/FLUS results and has a higher rate of malignancy.[20212728] Our results support that a repeat FNA offers a better selection of patients for further management. For cases with surgical follow-up, surgery was performed in 103 (56.9%) cases with a repeat FNA as compared to 78 (43.1%) cases without repeat FNA. The malignancy rate was 38.8% for cases with repeat FNA versus 25.6% for cases that went directly to surgery without a repeat FNA. Although beyond the scope of this study, repeat FNA may not be indicated in some cases based on suspicious clinical history or ultrasound findings.[17]

Some authors have suggested eliminating the AUS/FLUS category on the basis that the positive predictive value for most AUS/FLUS cases is similar to the FN category and a repeat FNA would not aid in patient management.[29] In our study, even though the overall malignancy rate (33.1%) is similar to that reported for FN/SFN (15-30%), cases where surgery was performed after the initial AUS/FLUS diagnosis were more likely to be benign (74.4%) as compared to those with repeat FNA (61.2%). Thus, a repeat FNA, for patients without further clinical suspicions, will spare patients from unnecessary surgery and its complications.[30] Therefore, we are of the belief that these comparable malignancy rates are a product of better clinical management and selection of patients diagnosed as AUS/FLUS for surgery after a repeat FNA.

In the current study, 181 thyroid nodules classified as AUS/FLUS that underwent surgical excision were equally divided as being aspirated under ultrasound-guidance by a team of radiologists and endocrinologists. Interestingly, the malignancy rate for nodules aspirated by radiologists (40.7%) was almost twice that of endocrinologists (25.6%). We believe that these results are indicative of operator experience, which may affect obtaining a representative sample from suspicious areas of the nodule (hypoechoic, solid and micro-calcifications) for cytologic interpretation.[3132333435]

CONCLUSION

We have shown that the diagnosis of AUS/FLUS is dependent on factors that are occurring at both pre-analytical and analytical phases of FNA evaluation of the thyroid nodule. These include experience of the operator obtaining the sample, variable diagnostic thresholds, and experience of the cytopathologist. Based on our study, even though the malignancy rate of AUS/FLUS cases is similar to those reported for cases diagnosed as FN/SFN, we are of the belief that these comparable malignancy rates are a product of better clinical management and selection of patients diagnosed as AUS/FLUS for surgery after a repeat FNA.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors of this article declare that we qualify for authorship as defined by the ICJME. Each author has participated sufficiently in the work and takes public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content of the article.

LQW is responsible for execution and analysis of the work and drafting the manuscript.

LQW, VAL and ZWB are responsible for planning and revising the article critically for important intellectual content.

ZWB is responsible for conceiving and coordinating the whole work, execution and analysis of the work and final approval of the version to be published.

Each author acknowledges that the final version was read and approved.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors take the responsibility of maintaining relevant documentation of records and other data used in this study as per the Institutional policy. All patient identifiers were suppressed in the final analysis of the data.

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double-blind model.(authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

REFERENCES

- The Bethesda System For Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;132:658-65.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thyroid fine-needle aspiration with atypia of undetermined significance: A necessary or optional category? Cancer. 2009;117:298-304.

- [Google Scholar]

- Analysis of the Bethesda system for reporting thyroid cytopathology and similar precursor thyroid cytopathology reporting schemes. Adv Anat Pathol. 2012;19:313-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Malignancy risk for fine-needle aspiration of thyroid lesions according to the Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology. Am J Clin Pathol. 2010;134:450-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Should “atypical follicular cells” in thyroid fine-needle aspirates be subclassified? Cancer Cytopathol. 2010;118:186-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evidence-based evaluation of the risks of malignancy predicted by thyroid fine-needle aspiration biopsies. Diagn Cytopathol. 2010;38:252-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnosis of follicular neoplasm in thyroid nodules by fine needle aspiration cytology: Does the result, benign vs. suspicious for a malignant process, in these nodules make a difference? Acta Cytol. 2009;53:517-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Subclassification of atypical cells of undetermined significance in direct smears of fine-needle aspirations of the thyroid: Distinct patterns and associated risk of malignancy. Cancer Cytopathol. 2011;119:322-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnostic criteria and risk-adapted approach to indeterminate thyroid cytodiagnosis. Cancer Cytopathol. 2010;118:415-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Usefulness of diagnostic qualifiers for thyroid fine-needle aspirations with atypia of undetermined significance. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;136:572-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and cytological features predictive of malignancy in thyroid follicular neoplasms. Thyroid. 2010;20:25-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Minimizing the diagnosis of “follicular lesion of undetermined significance” and identifying predictive features for neoplasia. Diagn Cytopathol. 2011;39:737-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thyroid Bethesda reporting category, ‘suspicious for papillary thyroid carcinoma’, pitfalls and clues to optimize the use of this category. Cytopathology. 2013;24:85-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- Does the fine-needle aspiration diagnosis of “Hürthle-cell neoplasm/follicular neoplasm with oncocytic features” denote increased risk of malignancy? Diagn Cytopathol. 2004;31:307-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Incidence of neoplasia in Hashimoto's thyroiditis: A fine-needle aspiration study. Diagn Cytopathol. 1996;14:38-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Spectrum of risk of malignancy in subcategories of ‘atypia of undetermined significance’. Acta Cytol. 2011;55:518-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thyroid follicular lesion of undetermined significance: Evaluation of the risk of malignancy using the two-tier sub-classification. Diagn Cytopathol. 2012;40:410-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Influence of descriptive terminology on management of atypical thyroid fine-needle aspirates. Cancer Cytopathol. 2014;122:175-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, Associazione Medici Endocrinologi, and European Thyroid Association Medical guidelines for clinical practice for the diagnosis and management of thyroid nodules: Executive summary of recommendations. Endocr Pract. 2010;16:468-75.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine-needle aspiration of follicular patterned lesions of the thyroid: Diagnosis, management, and follow-up according to National Cancer Institute (NCI) recommendations. Diagn Cytopathol. 2010;38:731-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Role of repeat fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) in the management of thyroid nodules. Diagn Cytopathol. 2003;29:203-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- The impact of atypia/follicular lesion of undetermined significance on the rate of malignancy in thyroid fine-needle aspiration: Evaluation of the Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology. Surgery. 2011;150:1234-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Utilization and impact of repeat biopsy for follicular lesion/atypia of undetermined significance. World J Surg. 2014;38:628-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Yield of repeat fine-needle aspiration biopsy and rate of malignancy in patients with atypia or follicular lesion of undetermined significance: The impact of the Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology. Surgery. 2012;152:1037-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Bethesda thyroid fine-needle aspiration classification system: Year 1 at an academic institution. Thyroid. 2009;19:1215-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- The prediction of malignant risk in the category “atypia of undetermined significance/follicular lesion of undetermined significance” of the Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology using subcategorization and BRAF mutation results. Cancer Cytopathol. 2014;122:368-76.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine-needle aspiration of thyroid nodules: A study of 4703 patients with histologic and clinical correlations. Cancer. 2007;111:306-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Incidence of malignancy in thyroid nodules determined to be follicular lesions of undetermined significance on fine-needle aspiration. World J Surg. 2012;36:69-74.

- [Google Scholar]

- Eliminating the “Atypia of undetermined significance/follicular lesion of undetermined significance” category from the Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;136:896-902.

- [Google Scholar]

- To operate or not to operate? The value of fine needle aspiration cytology in the assessment of thyroid swellings. J Clin Pathol. 1997;50:941-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Radiologic and clinical predictors of malignancy in the follicular lesion of undetermined significance of the thyroid. Endocr Pathol. 2013;24:62-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- The role of ultrasound findings in the management of thyroid nodules with atypia or follicular lesions of undetermined significance. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2014;80:735-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sonographic features of benign thyroid nodules: Interobserver reliability and overlap with malignancy. J Ultrasound Med. 2003;22:1027-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Is the anteroposterior and transverse diameter ratio of nonpalpable thyroid nodules a sonographic criteria for recommending fine-needle aspiration cytology? Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2005;63:689-93.

- [Google Scholar]