Translate this page into:

Is fine needle aspiration cytology a useful diagnostic tool for granular cell tumors? A cytohistological review with emphasis on pitfalls

*Corresponding author

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

Granular cell tumors (GCT) formerly known as Abrikossoff tumor or granular cell myoblastoma, are rare neoplasms encountered in the fine needle aspiration (FNA) service. Named because of their highly granular cytoplasm which is invariably positive for the S-100 antibody, the classic GCT is thought to be of neural origin. The cytomorphological features range from highly cellular to scanty cellular smears with dispersed polygonal tumor cells. The cells have abundant eosinophilic granular cytoplasm, eccentric round to oval vesicular nuclei with small inconspicuous nucleoli. The fragility of the cells can result in many stripped nuclei in a granular background. The differential diagnosis occasionally can range from a benign or reactive process to features that are suspicious for malignancy. Some of the concerning cytologic features include necrosis, mitoses and nuclear pleomorphism.

Methods:

We identified 6 cases of suspected GCT on cytology within the last 10 years and compared them to their final histologic diagnoses.

Results:

Four had histologic correlation of GCT including one case that was suspicious for GCT on cytology and called atypical with features concerning for a malignant neoplasm. Of the other two cases where GCT was suspected, one showed breast tissue with fibrocystic changes, and the other was a Hurthle cell adenoma of the thyroid.

Conclusions:

These results imply that FNA has utility in the diagnosis of GCT, and should be included in the differential diagnoses when cells with abundant granular cytoplasm are seen on cytology. Careful attention to cytologic atypia, signs of reactive changes, use of immunohistochemistry, and clinical correlation are helpful in arriving at a definite diagnosis on FNA cytology.

Keywords

Cytology

fine Needle aspiration

granular cell tumor

INTRODUCTION

Granular cell tumors (GCT) are rare neoplasms thought to be neuroectodermal in origin. However on fine needle aspiration (FNA), granular cell phenotype may be seen from nonneural entities such as oncocytic neoplasms of the breast and thyroid as well as smooth muscle or fibrohistioctyic tumors. They may arise anywhere in the body with a predilection for the skin, subcutaneous tissue and oral cavity[1] with the tongue being the single most common anatomic site involved. Histologic sections of GCTs show relatively consistent morphology while the cytologic appearance of GCT on needle aspiration is variable. The granular cytoplasm reflects the presence of secondary lysosomes and stains strongly for immunohistochemical markers S-100 and neuron specific enolase, as well as other melanocytic markers, CD68, inhibin, and calretinin. They are negative for keratin and muscle markers. Malignant GCTs are much rarer accounting for no more than 2-3% of all GCT. They present with size >4 cm, and show rapid growth and infiltrative borders. Suggested criteria for malignant GCTs include mitoses, necrosis, cellular pleomorphism, increased nuclear/cytoplasm ratios, vesicular nuclei with large nucleoli and high Ki-67 expression.[2] Perineural invasion can be seen in both benign and malignant tumors.[3] Because of the marked variability seen on cytologic smears, the differential diagnoses of GCT are many and include infection, inflammation and neoplasms, both benign and malignant.

This paper discusses the clinical features and origin of GCT and highlights the variable cytology seen on FNA preparations. Emphasis is placed on avoiding potential pitfalls by keeping in mind the vast differential diagnosis of an oncocytic lesion on FNA, paying close attention to the cytomorphological characteristics of GCT, as well as the use of special stains and immunohistochemistry on cell block preparations.

METHODS

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board. An electronic search of institutional cytopathology archives was conducted via the laboratory information system in order to identify cases of GCT. Six cases of suspected GCT within the previous 10 years were identified. The medical records of the patients were then reviewed for final diagnoses as well as histopathologic and clinical findings.

In all cases, the FNA of the palpable lesions was performed by a cytopathologist using a Cameco syringe holder and 22-23 gauge needles. The smears included air-dried preparations stained with a rapid Romanowski method for on-site evaluation and ethanol-fixed smears stained by the Papanicolaou method. The cytomorphology, histopathology and immunohistochemical stains (if any) were studied.

RESULTS

Of six cases, four were confirmed as GCT by histology. Of the other two cases that were suspected GCT bycytology, one was a breast mass discovered by routine mammography on a 78-year-old woman. Concomitant and subsequent biopsies showed benign breast tissue with fibrocystic changes and apocrine metaplasia. The other was a nontender, palpable thyroid nodule in a 44-year-old woman with systemic lupus erythematosus. Histologic evaluation of the thyroidectomy specimen rendered a diagnosis of Hurthle cell adenoma.

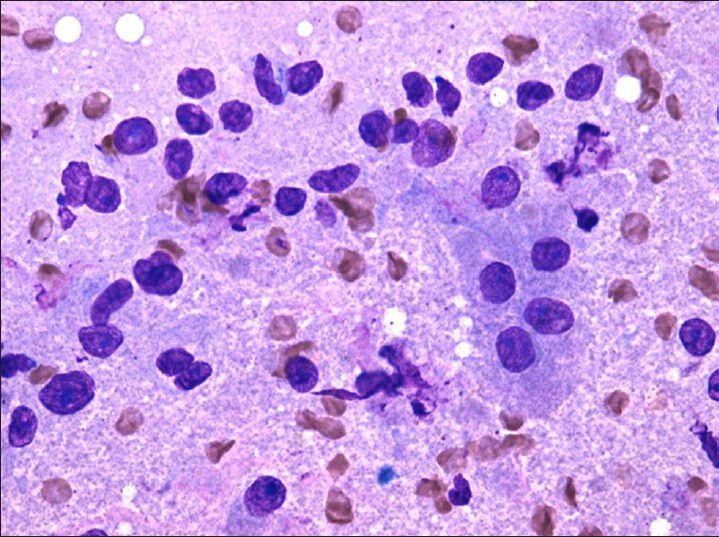

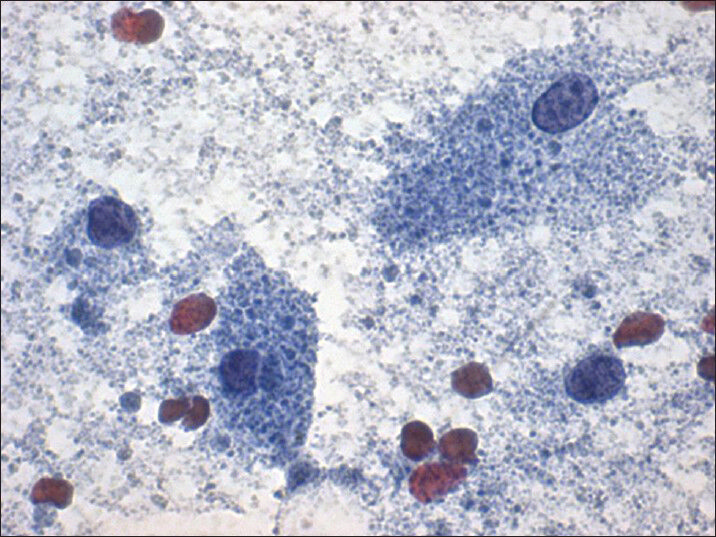

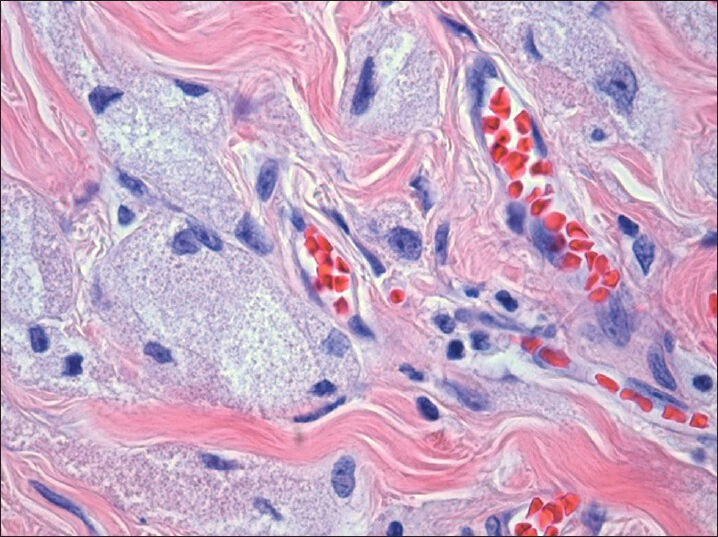

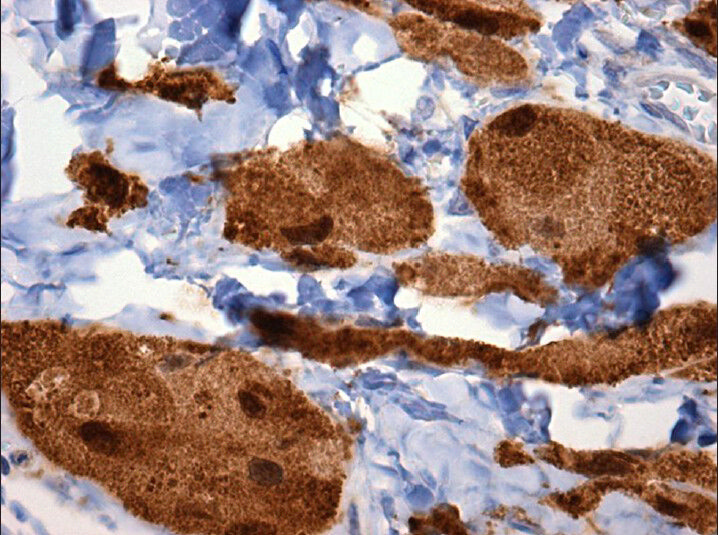

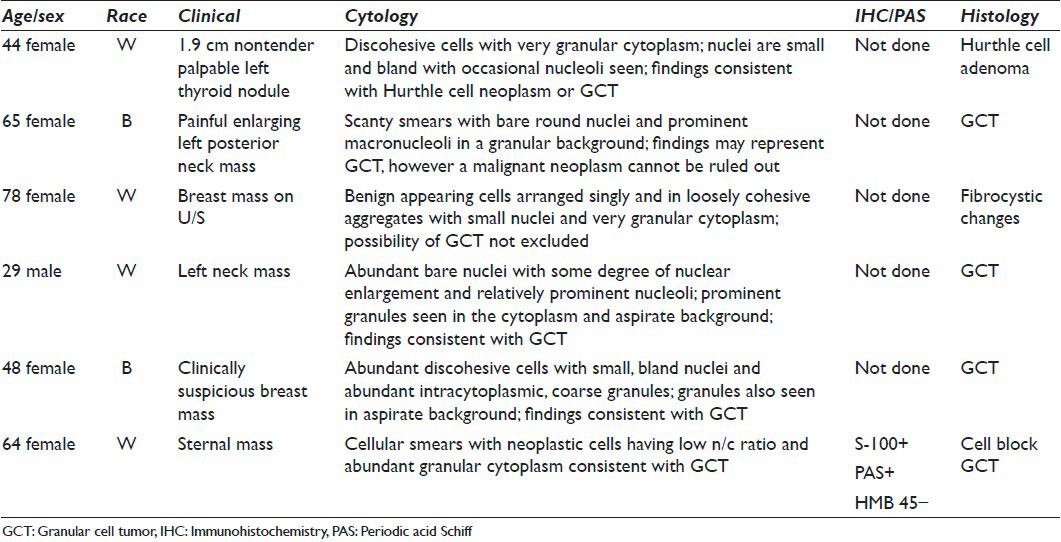

Of the cases that were proven to be GCT, one was a 65-year-old woman who presented with an enlarging, tender left posterior neck mass. FNA showed paucicellular smears with rare intact cells and bare, round nuclei within a pale, faintly granular background [Figures 1 and 2]. The nuclei demonstrated mild pleomorphism very prominent macronucleoli, but mitotic figures and necrosis were absent. The excisional biopsy showed a S-100 positive tumor [Figures 3 and 4]. Another case was a 29-year-old man presenting with a tender scalp mass. FNA showed abundant bare nuclei with mild nuclear enlargement and relatively prominent nucleoli. There were very distinct granules were noted in the cytoplasm and background. The results summary is given in Table 1.

- Diff-quik (×20) stains highlight intact cells with abundant granular cytoplasm and bare nuclei in a granular background

- Papanicolaou stain (×40) shows few intact cells with abundant granular cytoplasm and bland nuclei

- H and E, (×40) histologic section show infiltrative tumor with abundant granular cytoplasm and bland nuclei with small prominent nucleoli

- S-100 (×40) shows strong nuclear and cytoplasmic immuno reactivity

DISCUSSION

Granular cell tumor is a rare neoplasm encountered on FNA preparations that can closely mimic other conditions. These include benign and malignant neoplasms as well as infections. Most GCTs are benign, measuring <3 cm, often arise in the head and neck region including the oral mucosa, but can arise anywhere in the body and can be multifocal. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of the overlying epidermis or mucosa is common. Females and African-Americans are more affected than males and Caucasians respectively.

Granular cell tumor cytology show smears of naked nuclei within a coarsely granular background derived from the fragile cytoplasm of tumor cells. Specimen cellularity is variable ranging from scant to cellular preparations depending on the fibrosis associated with the lesion. When smears are paucicellular as was our case of the 65-year-old female with an enlarging left posterior neck mass, careful attention to the finely granular background is especially warranted as it may be the only clue pointing toward a GCT. Intact polygonal tumor cells are uniform and can occur as both syncytial groups and isolated cells. The cells show small round-to-oval nuclei with a minimal pleomorphism, ill-defined cell borders, and small but conspicuous nucleoli with abundant fine to coarse granular cytoplasm. The granules are periodic acid Schiff (PAS)-positive and diastase-resistant, and are believed to be lysosomes. Reported histologic Pustolo-ovoid bodies of Milan, which are aggregates of lysosomal granules, are rarely seen in cytology smears.[4] Cell blocks are of value as immunohistochemical stains for S-100 and CD 68 support the diagnosis of GCT. The CD 68 stains the lysosomes, and is not a specific histiocytic marker, as positivity may also seen in fibroblasts, dendritic cells, basophils, osteoclasts and tumors of these cells. GCTs are usually positive for vimentin, neuron-specific enolase (NSE), and negative for smooth muscle actin, desmin, actin, epithelial membrane antigen, cytokeratins, chromogranin, and HMB45. Electron microscopy supports a schwannian derivation.

The polygonal cells and fragile granular cytoplasm can often be mistaken for histiocytes and necrosis. Therefore, atypical infections, granulomatous inflammation, and histiocytic infiltrates must be considered in the differential diagnosis. Histiocytes however have smaller irregular or bean-shaped nuclei compared to the round to oval nuclei of GCT. Granulomatous inflammation consists of other inflammatory cells as opposed to pure population of neoplastic cells seen in GCT. Other benign nonneoplastic entities such as fat necrosis can cause similar findings. Neoplastic lesions in the differential diagnosis of GCT include rhabdomyomas, fibroxanthomas, dermatofibromas, oncocytic neoplasms, alveolar soft part sarcoma (ASPS) and metastatic renal cell carcinoma.[5] This is primarily due to the granular nature of their cytoplasm. Frequent cross-striations, “spider cells”, glycogen and negative S-100 immunostaining favors rhabdomyoma versus GCT. ASPS typically has frequent bi-and multinucleation, and pseudoacinar or pseudoalveolar architecture. Also, molecular studies of ASPS have demonstrated the chromosome rearrangement der (17) t (X; 17) (p11;q25),[6] while GCT has typically has no cytogenetic abnormalities. Renal cell carcinoma is S-100 negative and consists of scattered tumor cells with clear cytoplasm in contrast to GCT cells which contain uniformly granular cytoplasm.

A primary GCT of the thyroid gland is extremely uncommon with six reports seen in the literature.[7] Similar to GCT in general, these thyroid lesions are predominantly benign though metastasis has been reported.[8] Often these lesions are located in neck structures around or adjacent to the thyroid gland and are misdiagnosed as a primary thyroid neoplasm. Kintanar et al. reported a case of a GCT of the trachea that was initially interpreted as a thyroid follicular neoplasm with Hurthle cell change.[9] Histology showed similar features seen on cytology including uniform cells with abundant granular amphophilic cytoplasm. Immunohistochemical stains for S-100, NSE, and vimentin were positive rendering the diagnosis of GCT. A similar misdiagnosis of a GCT as a thyroid nodule has been seen in the esophagus.[10] Despite its rarity, GCT of the thyroid must be in the differential of a granular cell lesion and can be easily mistaken for a Hurthle cell neoplasm due to the inherent oncocytic nature of their cytoplasm. In our case, FNA smears showed findings seen in both GCT and a Hurthle cell neoplasm including polygonal cells with conspicuous nucleoli and granular cytoplasm. Borderline cases like ours illustrate the necessity of ancillary studies such as PAS stains and immunohistochemistry. Obvious cytoplasmic membranes and larger nuclei with more prominent nucleoli tend to point toward a Hurthle cell lesion.[11] A rare differential of GCT in the thyroid is black thyroid syndrome secondary to long-term minocycline therapy. Like GCT, cells of black thyroid syndrome have ill-defined borders and contain abundant granular cytoplasm. However, classic black thyroid findings include blue-gray cytoplasm with dark-brown granules and colloid can often be seen in the background.[12] Finally, because of the increased surveillance of thyroid nodules, a histiocytic reaction to a previous FNA should be considered. Histiocytes with foamy granular cytoplasm may mimic the cells of GCT, however the nuclei tend to be reniform as opposed to round and oval and the cytoplasm more foamy than granular. Increased inflammation, scarring, and hemosiderin pigment found in FNA biopsy sites help to distinguish them from GCT.

Similar pitfalls can be seen in breast masses. Generally, GCT of the breast is a rare lesion with approximately 225 cases reported.[13] Almost all reported cases of GCT have been located in the upper quadrants of the breast[14] and corresponds to the area of innervation of the supraclavicular nerve.[15] This correlates with the theory that GCT is derived from neural cells. These lesions are typically benign but can show clinical signs of malignancy such as an infiltrating spiculated lesion seen on breast imaging.[16] Their cytologic features can also mimic carcinoma.[17] The fragile granular cytoplasm of GCT can lead to a “dirty” background synonymous with necrosis that can be seen in breast carcinoma and other malignancies.[18] In the cases where GCT shows a degree of cellular and nuclear atypia, apocrine cancer and metastatic lesions such as renal cell carcinoma and melanoma must be ruled out.[16] This is accomplished with immunohistochemical stains such as S-100, vimentin, and CEA. Apocrine metaplasia, part of the fibrocystic changes spectrum seen in the breast, consists of benign epithelial cells with abundant eosinophilic granular cytoplasm and can be easily mistaken for GCT. The well-defined cellular borders of the apocrine-like breast epithelial cells versus the ill-defined borders seen in GCT is a clue to proper diagnosis. Also, the granularity of apocrine metaplasia is finer and pink on Romonowski stains compared to GCT, which is typically coarser and blue. Fat necrosis too can have granular background, however the cells have a foamy cytoplasm and multinucleated giant cells, and inflammatory cells are frequently seen.

Granular cell tumor is an uncommon neoplasm that can mimic many different diseases. The ability of GCT on FNA to appear as everything from benign histiocytes to malignant epithelial and mesenchymal cells can cause a diagnostic dilemma for practicing cytopathologist who may not have GCT on their differential. While FNA remains to be a critical, minimally-invasive diagnostic tool, our results underscores the necessity of ancillary studies such as immunohistochemistry and special stains. Awareness of this entity and its variable cytology, its differential diagnoses and careful clinical correlation are critical in accurate interpretation of findings.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors declare no competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors of this article declare that they qualify for authorship as defined by the ICMJE. All authors are responsible for the conception of this study, have participated in its design and coordination, and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

This study was conducted with approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the institution. Authors take responsibility to maintain relevant documentation in this report.

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double blind model (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

REFERENCES

- Colorectal granular cell tumor: A clinicopathologic study of 26 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:1186-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine needle aspiration cytology of a granular cell tumour arising in the thyroid gland. Cytopathology. 2012;23:411-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Multiple granular cell tumors of the tongue and parotid gland. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;107:e10-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pustulo-ovoid bodies of Milian in granular cell tumors. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:405-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Granular cell tumour on conventional cytology and thin-layer smears. Cytopathology. 2005;16:259-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- Alveolar soft part sarcoma: A single-center 26-patient case series and review of the literature. Sarcoma 2012 2012:907179.

- [Google Scholar]

- Granular cell tumour of the thyroid gland: A case report and review of the literature. Endocr Pathol. 2011;22:1-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- The importance of fine needle aspiration in conjunction with radiologic examination in the evaluation of granular cell tumor presenting as a thyroid mass: A case report. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2011;4:197-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Granular-cell tumor of trachea masquerading as Hurthle-cell neoplasm on fine-needle aspirate: A case report. Diagn Cytopathol. 2000;22:379-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Abrikossoff tumor of the proximal esophagus misdiagnosed as a thyroid nodule. Ann Chir. 2006;131:219-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Granular cell tumor of the breast preoperatively diagnosed by fine-needle aspiration cytology: Report of a case. Surg Today. 2004;34:760-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) of mammary granular cell tumour: A report of three cases. Cytopathology. 1999;10:383-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Granular cell tumor of the breast: Clinical and pathologic characteristics of a rare case in a 14-year-old girl. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:e656-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cutaneous granular cell tumor of the breast: A clinical diagnostic pitfall. J Clin Med Res. 2010;2:185-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Granular cell tumour: A pitfall in FNA cytology of breast lesions. Pathology. 2004;36:58-62.

- [Google Scholar]