Translate this page into:

Atypical endometrial cells and atypical glandular cells favor endometrial origin in Papanicolaou cervicovaginal tests: Correlation with histologic follow-up and abnormal clinical presentations

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

The 2001 Bethesda system recommends further classifying atypical glandular cells (AGCs) as either endocervical or endometrial origin. Numerous studies have investigated the clinical significance of AGC. In this study, we investigated the incidence of clinically significant lesions among women with liquid-based Papanicolaou cervicovaginal (Pap) interpretations of atypical endometrial cells (AEMs) or AGC favor endometrial origin (AGC-EM). More importantly, we correlated patients of AEM or AGC-EM with their clinical presentations to determine if AEM/AGC-EM combined with abnormal vaginal bleeding is associated with a higher incidence of significant endometrial pathology. All liquid-based Pap tests with an interpretation of AEM and AGC-EM from July, 2004 through June, 2009 were retrieved from the database. Women with an interpretation of atypical endocervical cells, AGC, favor endocervical origin or AGC, favor neoplastic were not included in the study. The most severe subsequent histologic diagnoses were recorded for each patient. During this 5-year period, we accessioned 332,470 Pap tests of which 169 (0.05%) were interpreted as either AEM or AGC-EM. Of the 169 patients, 133 had histologic follow-up within the health care system. The patients ranged in age from 21 to 71 years old (mean 49.7). On follow-up histology, 27 (20.3%) had neoplastic/preneoplastic uterine lesions. Among them, 20 patients were diagnosed with adenocarcinoma (18 endometrial, 1 endocervical, and 1 metastatic colorectal), 3 with atypical endometrial hyperplasia, and 4 with endometrial hyperplasia without atypia. All patients with significant endometrial pathology, except one, were over 40 years old, and 22 of 25 patients reported abnormal vaginal bleeding at the time of endometrial biopsy or curettage. This study represents a large series of women with liquid-based Pap test interpretations of AEM and AGC-EM with clinical follow-up. Significant preneoplastic or neoplastic endometrial lesions were identified in 20.3% of patients. Patients with Pap test interpretations of AEM or AGC-EM and the clinical presentation of abnormal vaginal bleeding should be followed closely.

Keywords

Abnormal vaginal bleeding

atypical endometrial cells

histologic follow-up

liquid based Pap test

INTRODUCTION

The Papanicolaou cervicovaginal (Pap) test was designed to screen squamous pathology of the cervix, and it has been a huge success in reducing the incidence of invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix for decades in the United States.[1] Although relatively uncommon, atypical glandular cell (AGC) interpretations show limited reproducibility and pose difficulties for both pathologists and the clinicians to manage those women with such an interpretation.[234]

The 2001 Bethesda System (TBS) terminology has incorporated changes to report glandular epithelial abnormalities.[5] Atypical glandular cells should be categorized as to the cell type of origin (endocervical or endometrial) whenever possible. Otherwise, the generic term “AGCs” can be used. These can be further classified as “favor neoplastic” or “not otherwise specified (NOS).” Atypical endometrial cell (AEM) needs not to be further classified.[6] The prevalence of AGC is low with a reporting rate of only 0.29% in a meta-analysis study.[7] There have been numerous studies addressing the clinical significance of patients with AGC in general.[891011121314151617] Histologic follow-up of women with an AGC interpretation has revealed a spectrum of lesions ranging from benign to malignant neoplasm and from squamous dysplasia to adenocarcinoma of the endocervix or endometrium.[9161819] The 2012 American Society of Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP) Guideline recommends endometrial and endocervical sampling for all women with a diagnosis of AEM.[20] If no endometrial pathology is revealed, then a subsequent colposcopy should follow. Clinicians are often more suspicious when the patients presented with postmenopausal bleeding to have significant endometrial pathology (atypical hyperplasia or adenocarcinoma). They often perform hysteroscopic examination and biopsy on patients with abnormal vaginal bleeding regardless of their Pap test results.[2122] Currently, there is limited published literature on the histological follow-up, specific for AEM or AGC favor endometrial origin (AGC-EM) on liquid-based Pap tests. Furthermore, the data on the correlation of Pap test cytology with clinical presentations at the time of biopsy (abnormal vaginal bleeding) is lacking.

Taking advantage of the uniform acceptance of TBS 2001 in our institution of AGC and a set of relatively objective criteria for AEM and AGC-EM, we conducted the current study to investigate the incidence of clinically significant lesions among women with liquid-based Pap interpretations of AEM and AGC-EM. In addition, we correlated these significant lesions with the patient's clinical presentation. The main objective of this study is to investigate if AEM/AGC-EM combined with abnormal vaginal bleeding is associated with higher incidence of significant endometrial pathology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This retrospective, cytohistologic correlation study was approved by the Cleveland Clinic's Institutional Review Board. During a 60-month period from July, 2004 to June, 2009, all ThinPrep® cases with AGC diagnoses from the Cleveland Clinic were collected. We fully adopted the TBS 2001 terminology for glandular cell abnormality.

During this 5-year period, we accessioned 332,470 Pap tests of which 169 (0.05%) were interpreted as either AEM or AGC-EM. Of the 169 patients, 133 had histologic follow-up within the health care system. These 133 patients comprise the current study population. Cases with the cytological interpretations of atypical endocervical cells, atypical glandular cells, NOS, atypical glandular cells, favor neoplastic, endocervical adenocarcinoma in-situ, or adenocarcinoma were excluded from the study.

We used the following cytomorphologic criteria for AEM and AGC-EM: (1) Nuclear enlargement, approximately two times of the size of the intermediate cell nucleus; (2) small, but visible nucleoli; and (3) groups of glandular cells with vacuoles containing neutrophils.

The most severe histopathologic diagnosis was recorded as the “end point.” The follow-up data were categorized as benign endometrium, endometrial polyp, endometrial hyperplasia without atypia, endometrial hyperplasia with atypia, and adenocarcinoma (endometrial, endocervical, or others).

The clinical notes were retrieved from the medical record. The presence or absence of abnormal vaginal bleeding was recorded on each patient.

In our institution, it is generally accepted that patients with cytological interpretations of AEM do not get HPV DNA test. On the other hand, patients with AGC-EM may get HPV-DNA test depend upon clinical judgment. Hybrid Capture 2 high-risk HPV DNA test (Qiagen Corp., Gaithersburg, MD, USA) was used to detect DNA from high-risk HPV types: 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, and 68.

Statistical comparisons were performed using the Fisher exact test, and the level of 0.05 was considered for significance. The SAS system (SAS Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used for the calculation.

RESULTS

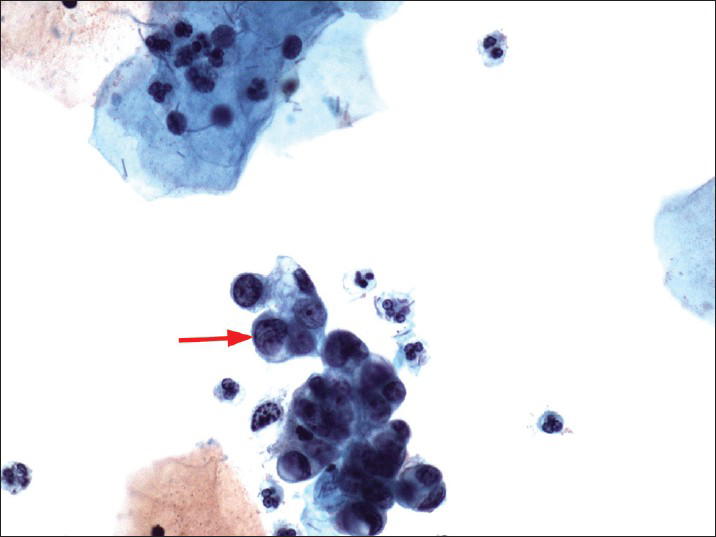

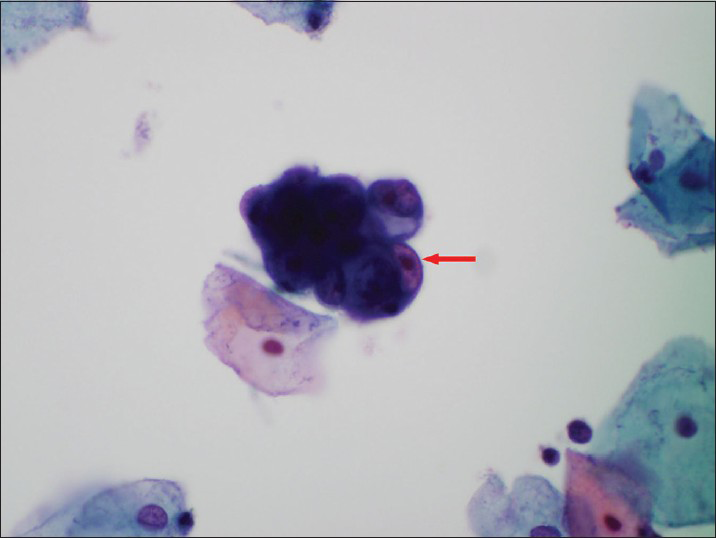

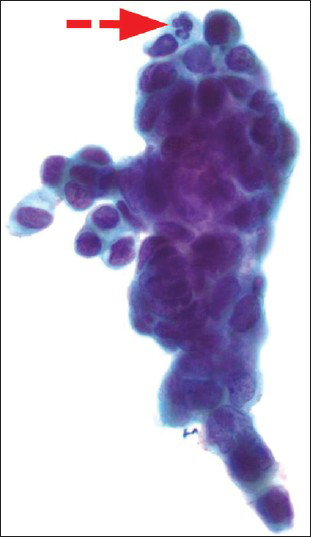

The patients ranged in age from 21 to 71 years old (mean 49.7). On ThinPrep® cytology slides, the 133 cases had at least one of the following cytological features of AEM or AGC-EM: (1) Nuclear enlargement, approximately two times of the size of an intermediate cell nucleus [Figure 1]; (2) small, but visible nucleoli [Figure 2]; and (3) groups of glandular cells with vacuoles containing neutrophils [Figure 3].

- A Papanicolaou cervicovaginal (Pap) test showing atypical glandular cells favors endometrial origin (nuclear size twice of that of an intermediate cell nucleus - red arrow). The histologic follow-up is well-differentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma, FIGO grade 1. Pap stain, ×400

- A Papanicolaou cervicovaginal (Pap) test showing atypical endometrial cells (a small group of glandular cells with visible nucleoli-red arrow). The histologic follow-up is atypical complex endometrial hyperplasia. Pap stain, ×600

- A Papanicolaou cervicovaginal (Pap) test showing atypical endometrial cells (a fairly large group of glandular appearing cells with cytoplasmic vacuole containing neutrophils-red arrow with dashed line). The histologic follow-up is well-differentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma, FIGO grade 1. Pap stain, ×600

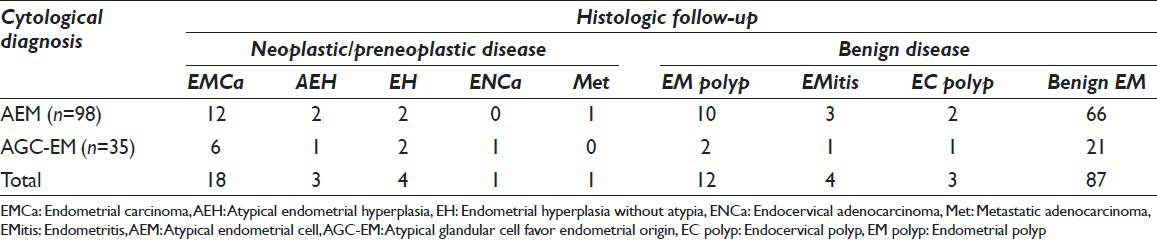

The time intervals between the Pap tests and histological follow-up ranged from <2 days to 4 months. On follow-up histology, 27 (20.3%) had neoplastic/preneoplastic uterine lesions. Among them, 20 patients (15%) were diagnosed with adenocarcinoma (18 endometrial, 1 endocervical and 1 metastatic colorectal carcinoma to the uterus), 3 (2.2%) with atypical complex endometrial hyperplasia, 2 had complex hyperplasia without atypia (1.5%), and 2 had simple hyperplasia without atypia (1.5%). The remaining 106 patients (79.7%) had nonneoplastic endometrial diseases: 12 had benign endometrial polyps (9.0%), 4 had chronic endometritis (3.0%), 3 had endocervical/isthmus-type polyp (2.3%), and 87 had benign endometrium (65.4%). Table 1 summarizes the initial cytology diagnosis and the histological correlation.

Of the 133 patients, 98 patients had the cytological diagnosis of AEM (73.7%), and 35 had the diagnosis of AGC-EM (26.3%). Sixteen of the 35 patients (45.7%) with AGC-EM had HPV DNA test. None of them was tested positive.

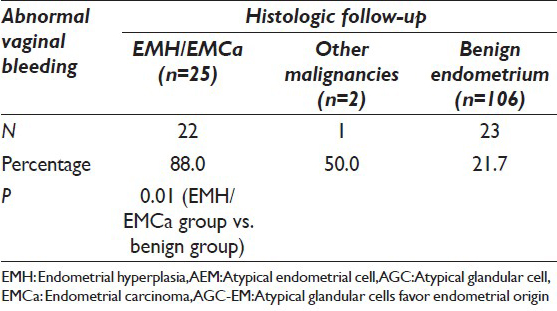

Among the patients with neoplastic/preneoplastic uterine lesions, 26 of 27 patients were over 40 years old (96.3%). Twenty-two of 25 patients (88.0%) with endometrial hyperplasia or adenocarcinoma presented with abnormal vaginal bleeding at the time of endometrial biopsy or curettage. The patient with metastatic colonic adenocarcinoma had abnormal vaginal bleeding. The patient with endocervical adenocarcinoma did not have abnormal bleeding. In contrast, only 23 of 106 (21.7%) patients of benign endometrial disease on followup presented with abnormal vaginal bleeding. This is significantly lower (P < 0.01) than the group of patients with neoplastic/preneoplastic endometrial disease. Table 2 compares the two groups of patients with the presence/absence of abnormal vaginal bleeding. The mean time interval between the Pap tests and biopsies among those patients with abnormal bleeding was much shorter than those patients without bleeding (7.4 days vs. 1.2 months, P < 0.05). There was no significant difference in the range of histologic diagnoses between the cases of AEM versus AGC-EM [Table 1].

DISCUSSION

The Pap test diagnosis of AGC is not common. However, patients with AGC are at higher risk for both significant glandular and squamous abnormalities.[23] It is well known that accurately classifying the atypical glandular cell of origin as being endocervical, endometrial, or squamous can be difficult.[4] The lack of well-defined cytomorphological criteria and the overlapping morphological features among atypical endocervical, atypical endometrial, and atypical squamous cells, cannot exclude high-grade squamous intraepithelial neoplasia (ASC-H) are major reasons for high interobserver variability when examining this subset of Pap tests.[2324] Nevertheless, the 2001 TBS terminology recommends that AGC should be categorized as to the cell type of origin (endocervical or endometrial) whenever possible.[6] Since most of the histological follow-up studies have included the generic group of AGC, we decided to conduct the current study to concentrate on those patients with the Pap test diagnoses of AEM and AGC-EM. Thus, we purposely excluded the cases with the Pap test diagnoses of AEC, AGC, favor endocervical, AGC-NOS, and AGC favor neoplastic. This study, to the best of our knowledge, represents the largest reported experience to date on histological follow-up of women with AEM/AGC-EM Pap test results.

Our data on histologic follow-up of women with AEM and AGC-EM are in keeping with the findings reported in the literature on both liquid based cytology and Pap smears.[252627] A small, but substantial subset of patients with AEM and AGC-EM Pap are found to have significant endometrial lesions. In addition, our study demonstrates several important clinical and pathological implications. First, most of the AEM/AGC-EM patients (88.0%) with endometrial hyperplasia or adenocarcinoma on follow-up presented with abnormal vaginal bleeding at the time of the endometrial biopsy/curettage. Our clinicians are very aware of the patient's abnormal clinical presentations. The mean time interval between the Pap tests and biopsies among those patients with abnormal bleeding was much shorter than those patients without bleeding (7.4 days vs. 1.2 months). Many of our clinicians would perform an endometrial biopsy regardless of whether or not the patient's Pap test is abnormal. These findings have not been well-documented in the cytology literatures. More importantly, our results recommend that clinicians should be on high alert when a patient with AEM/AGC-EM Pap test diagnosis presents with abnormal vaginal bleeding. Clinical management with endometrial biopsy/curettage is needed to exclude neoplastic/preneoplastic endometrial diseases.

Second, our study shows that AEM and AGC-EM Pap tests have a relative high specificity of predicting endometrial pathology. Only one patient in our study had endocervical adenocarcinoma, and none had high-grade cervical squamous dysplasia on histologic follow-up. This result may raise some questions. It is well-known that many cytopathologists, even the experienced ones, have some difficulty in confidently distinguishing AEM from AEC. However, in our institution, those ambiguous cases tend to be classified as AGC, NOS rather than AEM or AEC. Our study purposely excluded those cases of AGC, NOS. Furthermore, our result mirrors findings reported by a few others. Zhao et al. reported that only 1 cervical squamous dysplasia and no endocervical adenocarcinomas were detected in 99 AGC-EM cases (a subset of 662 AGC cases).[16] Similar findings are also observed in a previous retrospective follow-up study of women with AGC-EM. Chhieng et al. reported that only 3 of 62 women of AGC-EM had squamous dysplasia.[25] In our study, we used the following morphologic criteria once we encountered a small group of glandular cells on a Pap test to make distinction among normal and atypical endometrial cells or atypical endometrial, atypical endocervical, and possible HSIL cells involving endocervical glands: (1) enlarged nucleus (×2 the size of intermediate cell nucleus); (2) the presence of nucleoli; (3) cytoplasmic vacuoles with neutrophils. Salomao et al. studied 49 conventional smears of AGC-EM and also found that besides an atrophic smear background and absence of clusters with irregular borders, nuclear size larger than twice that of an intermediate cell nucleus is an important cytologic feature indicative of endometrial malignancy.[26] Zhou et al. have shown that in Pap tests, enlarged nuclei and the presence of nucleoli are reliable diagnostic criteria to make distinctions among normal, atypical, and endometrial adenocarcinoma cells.[28] The set of criteria we used in our study are relatively objective and have demonstrated a reliable distinction among atypical endometrial cells, atypical endocervical cells, and ASC-H cells.

Third, although HPV DNA tests were ordered on 45.7% of AGC-EM cases in our study, none of them is positive for high-risk HPV. This result is expected. HPV DNA testing is recommended in 2012 ASCCP follow-up guidelines of women with AGC Pap results, not as an initial reflex test, but as an additional ancillary test to follow initial colposcopic evaluation and endocervical sampling.[20] Reflex or co-test for high-risk HPV DNA testing has been shown to increase the sensitivity and specificity of detecting significant cervical lesions among women with AEC or AGC, favor endocervical origin or AGC, NOS on cytology.[293031] However, HPV DNA testing does not have added value for detecting endometrial hyperplasia/adenocarcinoma. Zhao et al. found in their study that HPV testing after an AGC Pap was not useful in the detection of endometrial and ovarian carcinoma in women older than 50.[32] Our results support the recommendation of TBS to further classify AGC to the cell of origin whenever possible. HPV DNA testing is useful in women with AGC-EC or AGC, NOS, but should not be performed on AEM or AGC-EM.

In summary, this is a large cytologic-histologic correlation study on AEM and AGC-EM designed to evaluate the diagnostic value of the ThinPrep® Pap test in the detection of endometrial hyperplasia/adenocarcinoma. Furthermore, patients with abnormal clinical presentations are correlated with Pap test findings of AEM and AGC-EM. Our data demonstrate that AEM and AGC-EM Pap tests have a relative high specificity of predicting endometrial pathology. Patients with Pap test interpretations of AEM or AGC-EM and the clinical presentation of abnormal vaginal bleeding should be followed closely.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors declare no competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors of this article declare that they qualify for authorship as defined by the ICMJE. All authors are responsible for the conception of this study, have participated in its design and coordination, and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

This study was conducted with approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the institution. Authors take responsibility to maintain relevant documentation in this report.

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double blind model.(authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

REFERENCES

- The Papanicolaou test for cervical cancer detection. A triumph and a tragedy. JAMA. 1989;261:737-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- Interobserver variability of a Papanicolaou smear diagnosis of atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance. Am J Clin Pathol. 1998;110:653-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Glandular cell atypia on Papanicolaou smears: Interobserver variability in the diagnosis and prediction of cell of origin. Cancer. 2003;99:323-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Can we improve the detection of glandular cervical lesions: The role and limitations of the Pap smear diagnosis atypical glandular cells (AGC) Gynecol Oncol. 2009;114:381-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Second edition of ‘The Bethesda System for reporting cervical cytology’-Atlas, website, and Bethesda interobserver reproducibility project. Cyto J. 2004;1:4.

- [Google Scholar]

- The 2001 Bethesda system: Terminology for reporting results of cervical cytology. JAMA. 2002;287:2114-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rate of pathology from atypical glandular cell Pap tests classified by the Bethesda 2001 nomenclature. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:1285-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of cervical disease history on outcomes of women who have a pap diagnosis of atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance. Gynecol Oncol. 1999;74:460-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Histologic implications of Pap smears classified as atypical glandular cells. J Reprod Med. 2005;50:539-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinicopathological significance of atypical glandular cells on Pap smear. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2013;56:76-83.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical evaluation of follow-up methods and results of atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance (AGUS) detected on cervicovaginal Pap smears. Gynecol Oncol. 1999;73:292-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Follow-up study of atypical glandular cells in gynecologic cytology using conventional Pap smears and liquid-based preparations: Impact of the Bethesda system 2001. Acta Cytol. 2008;52:159-68.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical significance of atypical glandular cells on Pap smears: Experience from a region with a high incidence of cervical cancer. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2011;37:496-500.

- [Google Scholar]

- Outcomes of pregnant patients with Pap smears classified as atypical glandular cells. Cytopathology. 2012;23:383-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical significance of atypical glandular cells in conventional pap smears in a large, high-risk U.S. west coast minority population. Acta Cytol. 2009;53:153-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Histologic follow-up results in 662 patients with Pap test findings of atypical glandular cells: Results from a large academic womens hospital laboratory employing sensitive screening methods. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;114:383-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Identification of atypical glandular cells in pap smears: Is it a hit and miss scenario? Acta Cytol. 2013;57:45-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- Atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance Pap smears: Appropriate evaluation and management. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2000;12:33-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Histologic and clinical significance of atypical glandular cells on pap smears. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005;91:238-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2012 updated consensus guidelines for the management of abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121:829-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- Practice guideline: Evaluation and management of abnormal vaginal bleeding in adolescents. J Pediatr Health Care. 2009;23:189-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Management of postmenopausal women with vaginal bleeding when the endometrium can not be visualized. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2012;91:686-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Bethesda Interobserver Reproducibility Study (BIRST): A web-based assessment of the Bethesda 2001 system for classifying cervical cytology. Cancer. 2007;111:15-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical implications of atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance, favor endometrial origin. Cancer. 2001;93:351-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance favor endometrial origin. Criteria for separating low grade endometrial adenocarcinoma from benign endometrial lesions. Acta Cytol. 2002;46:458-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical significance of a cytologic diagnosis of atypical glandular cells, favor endometrial origin, in Pap smears. Acta Cytol. 2006;50:48-54.

- [Google Scholar]

- The diagnostic value of the ThinPrep pap test in endometrial carcinoma: A prospective study with histological follow-up. Diagn Cytopathol. 2013;41:408-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Human papillomavirus DNA detection and histological findings in women referred for atypical glandular cells or adenocarcinoma in situ in their Pap smears. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;95:618-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of reflex human papillomavirus DNA testing in patients with atypical endocervical cells on cervical cytology. Cancer. 2008;114:236-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- The utility of human papillomavirus testing in young women with atypical glandular cells on pap test. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2014

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical utility of adjunctive high-risk human papillomavirus DNA testing in women with Papanicolaou test findings of atypical glandular cells. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:103-8.

- [Google Scholar]