Translate this page into:

The Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology: An outcome of retrospective application to three years’ cytology data of a tertiary care hospital

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Singh G, Jahan A, Yadav SK, Gupta R, Sarin N, Singh S. The Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology: An outcome of retrospective application to three years’ cytology data of a tertiary care hospital. CytoJournal 2021;18:12.

HTML of this article is available FREE at: https://dx.doi.org/10.25259/Cytojournal_1_2021

Abstract

Objectives:

Fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) of the salivary gland lesions has diverse and sometimes overlapping features that pose a diagnostic challenge for the cytopathologists. The Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology (MSRSGC) has been introduced to bring uniformity in the reporting of salivary gland FNAC and improve the clinic-pathologic communication resulting in better patient management. The aim of the present study was to assess the application of the MSRSGC on FNAC specimens of salivary gland lesions at a tertiary care hospital.

Material and Methods:

All salivary gland aspiration cytology cases along with histopathology follow-up of salivary gland lesions, wherever available, over a period of 36 months were analyzed and re-categorized according to MSRSGC into six categories and the risk of malignancy (ROM) was computed.

Results:

Of the 123 patients, 23 (18.69%) were classified as non-diagnostic, 39 cases (31.7%) as non-neoplastic, one (0.81%) as atypia of undetermined significance (AUS), benign neoplasm in 49 (39.8%) cases, uncertain malignant potential in two cases (1.63%), suspicious of malignancy in two cases, and malignant in seven cases (5.69%). Out of 123 cases, histopathological correlation was available in 34 cases, for which the ROM was calculated. The ROM was 0% for non-neoplastic, 11.1% for benign neoplasm, and 100% each for salivary neoplasm of uncertain neoplastic potential, and 100% for malignant categories.

Conclusion:

In the present study, the distribution of cases according to MSRSGC was comparable with the previous studies. The proportion of cases classified as AUS was within the goal set by MSRSGC at less than 10%. A risk-based stratification of salivary gland lesions in the form of MSRSGC is essential in the present era to guide and alert the clinician about the subsequent management plan and convey the ROM.

Keywords

Milan system

Salivary gland

Cytology

Histopathology

Malignancy

INTRODUCTION

Salivary gland lesions constitute 3–6% of all lesions of head and neck region.[1] At present, the initial diagnostic workup of a salivary gland lesion utilizes a multimodal approach, comprising imaging studies such as ultrasonography and/or magnetic resonance imaging for localization of the lesion, followed by fine-needle aspiration (FNA) cytology for typing and classification.[2,3] FNA cytology has been reported to be a sensitive (54–98%) and specific (88–98%) modality for diagnosis of salivary gland lesions allowing for appropriate pre-operative management decisions.[4-7] However, the heterogeneity of cytomorphological features and frequent overlap of features between various lesions lead to instances of inter-observer disagreement on cytologic diagnosis.[3,5]

In line with the Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology[8] and The Bethesda System for Reporting Cervical Cytopathology,[9] a user-friendly and internationally-accepted category-based system for cytologic diagnosis of salivary gland lesions have been devised. The Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology (MSRSGC) includes a six-category diagnostic scheme with explanatory notes, implied risk of malignancy (ROM), and a brief management plan for each diagnostic category.[10] The MSRSGC has been evaluated by few authors demonstrating the usefulness of this system in reporting salivary gland lesions and thus facilitating individualized management.[11-13]

However, till date, only scant literature is available depicting the usefulness and reproducibility of the MSRSGC system. The few studies in English literature lacked uniformity in the inclusion of all categories of MSRSGC, and hence have demonstrated variable ROM for each of the six categories of MSRSGC.[11-16]

The present study was aimed at assessing the utility of MSRSGC categorization on FNA specimens of salivary gland lesions in stratifying the ROM in these cases at a tertiary level hospital.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

A total of 123 cases of salivary gland FNA were performed over a period of 3 years (2017–2019). Of these, histopathology follow-up was available in 34 cases. Fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNACs) was performed under aseptic conditions using 10 ml syringe with 22/23-gauge needles. Depending on the size and complexity of the lesion, one to four needle passes were undertaken. Air dried smears were stained using May Grünwald Giemsa stain and a few smears were wet-fixed for Pap stain. For histopathological examination, formalin-fixed, surgically resected specimen and/or biopsy tissues were paraffin processed and stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin.

FNA smears were reviewed and reported by a senior pathologist as per Milan System into six categories. The six categories of Milan system were as follows – Category I (Non-diagnostic), Category II (Non-neoplastic), Category III (Atypia of Undetermined Significance [AUS]), Category IVa (benign), Category IVb (Salivary gland neoplasm of Uncertain Malignant Potential [SUMP]), Category V (Suspicious for Malignancy [SFM]), and Category VI (Malignant).

The reviewing cytopathologist was blinded to the initial cytologic diagnosis as well as the final clinical and/or surgical follow-up. Cases with discordance between the Milan Category diagnosis and the initial diagnosis were reviewed by another senior pathologist for consensus and final categorization. ROM was calculated in the 34 cases having histopathological follow-up.

RESULTS

Of total 123 patients, 68 (55.28%) were males and 55 (44.72%) were females, with a male:female ratio of 1.25:1. Maximum number of patients was in the fifth decade of life, constituting 25.2% of total number of cases. The mean age was 36.5 years, the youngest being 4 years and the oldest 83 years old. The most common site of involvement was the parotid gland (73 cases; 59.35%), followed by submandibular gland (44 cases; 35.77%) and minor salivary glands (4 cases; 3.25%).

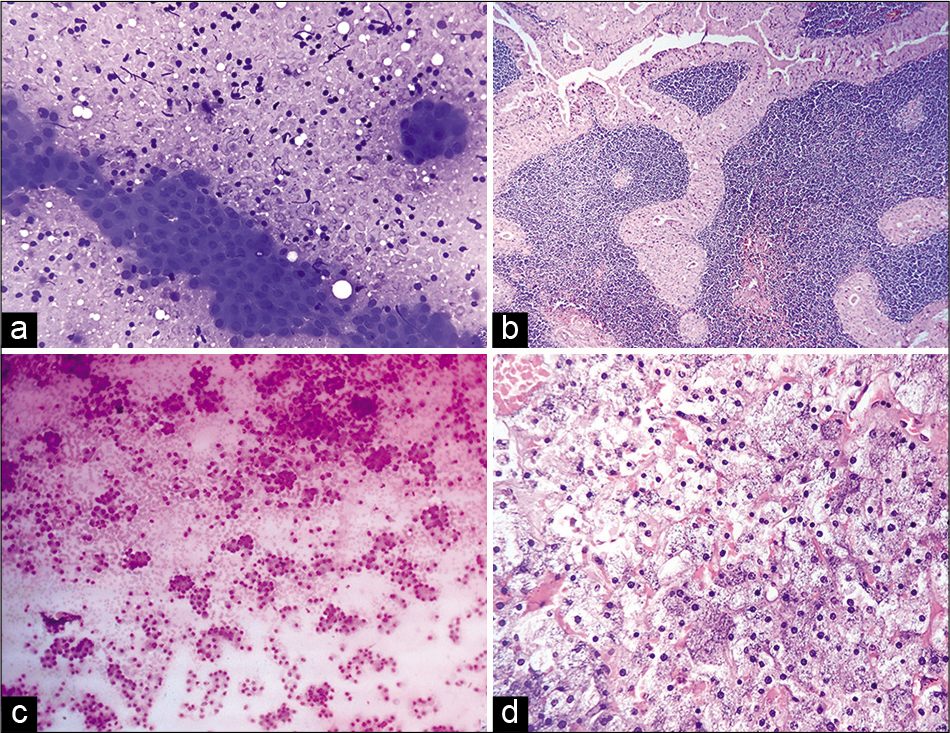

As per the MSRSGC classification system, 63 cases were categorized as non-neoplastic while 60 as neoplastic lesions. Of the non-neoplastic cases, 23 (18.69%) were grouped in Category I, 39 cases (31.7%) in Category II, and one case (0.81%) in Category III. Out of the 60 salivary gland neoplasms, 49 (39.8%) cases were in Category IVa [Figure 1a and b], two (1.63%) cases in Category IVb, two (1.63%) cases in Category V, and seven (5.69%) cases in Category VI [Figure 1c and d]. These category-wise results are tabulated in Table 1. There were no cases of discordance between the initial cytopathologic diagnosis and MSRSGC categorization.

- (a) Cytosmear of a case categorized as IVa of MSRSGC showing sheets of oncocytic cells in a lymphoid background (MGG, ×40). (b) Microsection of the same case as in A showing a papillary structure lined by bi-layered oncocytic epithelium with lymphoid cells in the core (H&E, ×10). (c) Cytosmear of a case of acinic cell carcinoma showing loosely cohesive clusters of monomorphic cells with finely vacuolated moderate cytoplasm (MGG, ×10). (d) Hisopathologic photomicrograph of the same case as in C reported as acinic cell carcinoma (H&E, ×10).

| Milan category | Milan category (n,%) | Initial cytopathological diagnosis | No. of cases | Histopathological follow-up | ROM in present study | ROM as per MSRSGC[11] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Non-diagnostic | Normal salivary gland tissue | 08 | - | 0% | Up to 25% |

| 23 (18.7%) | Blood only | 07 | - | |||

| Acellular | 01 | Normal salivary gland tissue with lymphoid follicles (1) | ||||

| Cyst fluid only | 07 | Warthin’s tumor (1) | ||||

| Retention cyst (1) | ||||||

| II | Non neoplastic | Inflammatory | 3 | - | 0% | Up to 10% |

| 39 (31.7%) | Abscess | 3 | - | |||

| Chronic sialadenitis | 20 | Chronic sialadenitis (5) | ||||

| Granulomatous sialadenitis | 1 | - | ||||

| Chronic sialadenitis/LEL | 3 | - | ||||

| Acute sialadenitis | 2 | - | ||||

| Sialadenosis | 7 | - | ||||

| III | Atypia of Undetermined Significance | Lymphoepithelial cyst/ WT | 1 | WT (1) | 0% | Up to 20% |

| 1 (0.81%) | ||||||

| IVa | Benign neoplasm | PA | 45 | Pleomorphic adenoma (15) | 11.1% | <5% |

| 49 (39.8%) | Atypical PA (1) | |||||

| PA with foci of EMC (1) | ||||||

| Benign adenoma | 3 | - | ||||

| WT | 1 | WT (01) | ||||

| IVb | Salivary gland neoplasm of uncertain malignant potential | Salivary gland neoplasm | 2 | Acinic cell carcinoma (1) | 100% | ~35% |

| 2 (1.63%) | MECa (1) | |||||

| V | Suspicious for malignancy | Low grade MECa/ WT | 01 | MECa (1) | 100% | ~60% |

| 2 (1.63%) | ACC/PLGA | 01 | ACC (1) | |||

| VI | Malignant | MECa | 2 | - | 100% | ~90% |

| 7 (5.69%) | ACC/Basal cell adenocarcinoma | 1 | ACC (1) | |||

| Small cell SGN | 1 | - | ||||

| Malignant salivary gland neoplasm | 2 | MECa (1) | ||||

| Acinic cell carcinoma | 1 | Acinic cell carcinoma (1) |

LEL: Lymphoepithelial lesion, WT: Warthin’s tumor, PA: Pleomorphic adenoma, EMC: Epithelial myoepithelial carcinoma, MECa: Mucoepidermoid carcinoma, ACC: Adenoid cystic carcinoma, PLGA: Polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma, SGN: Salivary gland neoplasm

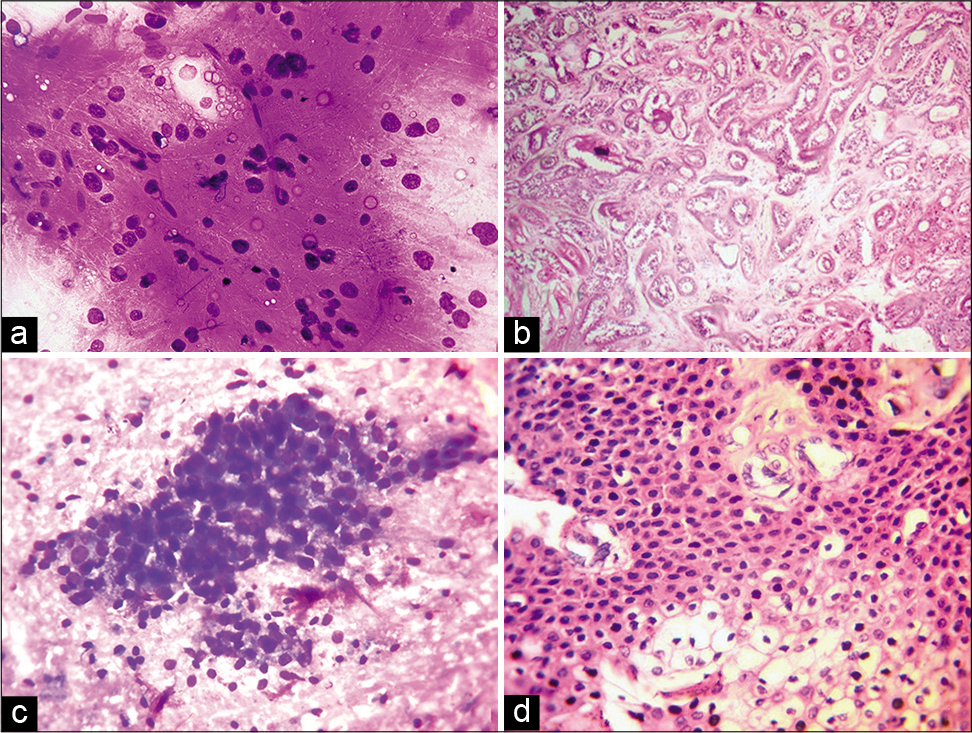

Surgical follow-up was available in 34 (27.64%) cases. Out of these 34 cases, cytohistological concordance was noted in 31 cases (91.2%), as seen in Table 1. Two cases reported as benign on FNAC (Category IVa), were diagnosed as pleomorphic adenoma (PA) with foci of epithelial myoepithelial carcinoma (EMC) [Figure 2a and b] and atypical PA, respectively, on histopathology. One case placed in Category III on cytology was diagnosed as Warthin’s tumor on histopathology. The ROM was calculated for each category as depicted in Table 1.

- (a) Cytosmear of a case of pleomorphic adenoma showing chondromyxoid material with embedded epithelial/myoepithelial cells (MGG, ×10). (b) Microsection of the case in A showing features of epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma with infiltrating glands lined by epithelium as well as myoepithelial cells with clear cytoplasm (MGG, ×10). (c) Cytosmear of a case reported as Category 5 of MSRSGC, showing loosely cohesive clusters of cells with mild to moderate cytoplasm and round nucleus with mild nuclear atypia (MGG, ×40). (d) Microsection of case shown in (b) reported as mucoepidermoid carcinoma on histopathology (H&E, ×40).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, the age range and gender distribution of the salivary gland lesions was like previous studies.[11,12,14] As with other reports,[15,16] parotid gland was the most frequently involved gland (59.35%) followed in decreasing order of frequency by submandibular glands (35.77%), sublingual gland (1.63%), and minor salivary glands (3.25%).

FNA has increasingly gained importance as the preferred pre-operative diagnostic tool for the evaluation of a salivary gland lesion and providing useful information for clinical management decisions. However, in lesions showing diverse morphology and various forms of metaplasia, cytomorphological interpretation tends to become challenging. Till recently, there have been many different classification formats being followed for salivary gland cytology such as the five-group system (Myxoid-hyaline, basaloid, oncocytoid, lymphoid, and squamoid lesions) suggested by Miller.[17] Tessy et al. classified the salivary gland lesions as inflammatory, benign, malignant, and others.[18,19] Some authors advised the use of a three-tier system, that is, non-neoplastic lesions, benign, and malignant tumors.[20] The wide variety of classifications systems being used for salivary gland cytology has hampered inter-laboratory and clinic-pathological correlations. Hence, to harmonize the reporting of salivary gland FNAs and to improve the communication between cytopathologists and clinicians, MSRSGC was formulated by the American Society of Cytopathology and the International Academy of Cytology in 2017.[10] This system includes six categories of salivary gland lesions. The present study aimed to evaluate the application of MSRSGC to salivary gland aspirates in a tertiary level hospital.

In the present study, 23 cases (18.69%) were unsatisfactory for diagnosis (Category I) due to scant cellularity on aspirate. The most common reason for the inadequacy was fluid aspirate from a cystic lesion. The frequently encountered non-tumorous cysts in salivary gland are retention cysts, mucoceles and lymphoepithelial cysts while neoplasms such as mucoepidermoid carcinoma, Warthin’s tumor, acinic cell carcinoma, cystic PA, and cystadenoma may also present as cystic lesions.[21] Hence, in cystic lesions, it is advised to undertake post-evacuation FNA with multiple passes from variable places to reduce the false-negative reports.[21] The proportion of salivary gland aspirates reported as unsatisfactory in the literature varies from as low as 2.08%[11]–18.8%,[22] similar to the present study. In the present study, three of the unsatisfactory cases underwent surgical intervention. One of them was reported as a Warthin’s tumor while the other two were non-neoplastic (normal salivary gland tissue in one case and retention cyst in the other).

Non-neoplastic lesions or Category II were the most common salivary gland lesions in the present study (31.7%). On review of literature, similar distribution of Category II cases (21.5%– 38.2%) was reported by other authors as well,[11,13,22] though a higher proportion (55.8%) was reported by Rohilla et al.[21] Chronic sialadenitis was the most common cytological diagnosis in our study followed by sialadenosis, like the previous reports.[16,23] In our study, five of the cases in this category had histopathological correlation and all of them showed concordant diagnosis. The ROM in this category was 0% in our study, though up to 10% ROM for non-neoplastic category has been reported by some authors.[5]

AUS category or Category III in the MSRSGC is defined as a salivary gland lesion that lacks either qualitative or quantitative cytomorphologic features to be diagnosed with confidence as either non-neoplastic or neoplastic.[23] The ROM has not been defined accurately for this category, though it ranges between 20 and 100%, primarily dependent on the cases included in this category in the various studies.[11-14,21] According to Wangsiricharoen et al., the ROM was highest for specimen in AUS category with preparation artifact subtype.[24] As with all the classification systems, cytopathologists need to be careful while categorizing a case as AUS. In our study, only one case (0.81%) was categorized into Category III, which complies with the goal of MSRSGC to keep the FNA labeled as atypical to less than 10% of all salivary gland aspirates. In this patient, the cytosmear showed granular cystic background, few oncocytic cells in groups along with scattered lymphocytes. The differentials of lymphoepithelial cyst and Warthin’s tumor were considered on aspiration cytology. Since the distinction between a non-neoplastic lesion and benign tumor was not clear, the case was placed in category III. On histopathological follow-up, this case was reported as a Warthin’s tumor.

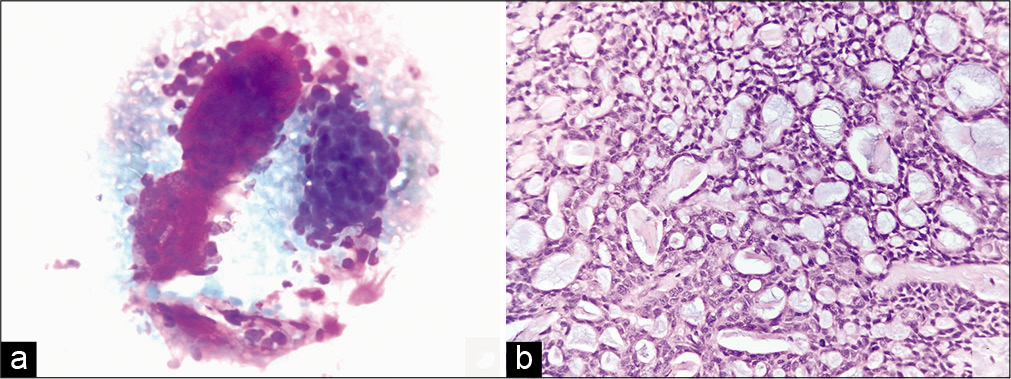

In the present study, a total of 60 cases (48.7%) were categorized into neoplastic lesions (Category IV, V, VI). Out of these, 49 cases were benign (IVa), two cases were SUMP, IVb, two cases were SFM (V), and seven cases were malignant (VI). PA was the most common (88.23%) benign salivary gland tumor (IVa). while mucoepidermoid carcinoma was the most common (28.6%) malignant salivary gland tumor (VI). The predominance of these two neoplasms was like those previously reported in a few studies.[21,23,25,26] Among the 45 cases of PA, 17 underwent surgical excision. Cytohistological correlation was seen in 15 of the 17 resected cases of PA. One case, on histopathology, showed atypical nuclear features with high Ki-67 labeling index and was labeled as atypical PA while the other showed foci of EMC within a PA. In the present study, two cases were classified in Category IVb (SUMP). Both these cases were initially reported as salivary gland neoplasm on the FNAC. Of these, the cytosmears in one case were paucicellular comprised of small groups and loosely cohesive clusters of cells having well-defined non-vacuolated cytoplasm in a hemorrhagic background. This case was reported as acinic cell carcinoma on histopathological follow-up. The second case, on FNAC, showed sheets of cells with moderate to abundant amount of cytoplasm and normochromatic small nuclei in proteinaceous background in cytology smears. No other cell type was seen on cytology. This was reported as mucoepidermoid carcinoma on subsequent histopathology. Earlier studies have shown the ROM in SUMP category to be different based on the predominant cellular features, risk being lower for tumors with oncocytic features compared to those with basaloid pattern.[27] The two cases in Category V (SFM) in the present study were diagnosed as mucoepidermoid carcinoma [Figure 2c and d] and adenoid cystic carcinoma, respectively, giving a ROM of 100% for this category. The overall prevalence of malignancy for Group VI as observed by other authors varies from 9.4 to 51%.[11-13,22,28] In the present study, malignant cases (Category VI) comprised 5.69% of all salivary gland lesions and 11.67% of the neoplastic masses. Cyto-histologic correlation was available in three out of the seven malignant cases [Figure 3a and b] in our study with a ROM of 100%, as proposed by MSRSGC and reported by Rossi et al. and Griffith et al.[5,29] The rest of these cases were lost to follow-up. The major challenges of calculating the ROM in various categories and its clinical applicability are the limited number of surgical follow-ups available. A bias in the form of only neoplastic lesions getting excised leading to overestimation of ROM has also been suggested by few authors.[21]

- (a) Cytosmear of a case of adenoid cystic carcinoma showing cluster of cells with extremely scanty cytoplasm. Also seen is a pink stromal material having smooth outline (MGG, ×40). (b) Microsection of case shown in Figure 3a reported as adenoid cystic carcinoma on histopathology (H&E, ×40).

In the present study, there were three instances of discordance: One in Category III and two cases in IVa. One case was placed in Category III due to cystic nature, presence of scant number of oncocytic cells and variable number of lymphocytes. On histopathological follow-up, this case was diagnosed as Warthin’s tumor. Warthin’s tumor on cytology can lead to both false-positive and false-negative diagnosis mainly due to sampling error that can result in predominance of metaplastic squamous cells or only epithelial cells with cyst macrophages, and variable numbers of lymphocytes (nil to abundant).[21] One of the cases in Category IVa, diagnosed as PA on FNA, was reported as EMC on histopathology with S-100 positivity in the myoepithelial cells. In this case, the cytosmears showed bland epithelial cells, spindly cells, and few bare nuclei along with scant myxoid stroma. The characteristic cytopathological features of EMC – three-dimensional cellular aggregates, peripheral clear cells and presence of acellular hyaline material – may not be seen in all cases and hence, the cytological diagnosis is rendered difficult.[30] Another Category IVa case, cytologically diagnosed as PA, was reported as atypical PA with high Ki-67 labeling index histopathologically. No evidence of extracapsular invasion was noted in this case. Both these entities may be difficult to be recognized on aspiration cytology, especially given the sampling bias and the diagnostic challenge in differentiation of epithelial-myoepithelial neoplasm from PA.[30]

The distribution of our cases according to MSRSGC is comparable with the previous studies published in English literature.[11-13,22] Our study suffers from few limitations such as the small sample size, lesser number of histological follow-up, and the retrospective nature of the study. However, being a tertiary care center, a wide array of cases from both nonneoplastic and neoplastic spectrum could be included in our study.

Thus, the Milan system of reporting salivary gland cytology provides a useful and uniform 6-tier reporting approach of salivary gland lesions helping in risk stratification and guidance for further management. A risk-based stratification is essential in the present era to guide and alert the clinician about the subsequent management plan and convey the ROM in various categories. False-negative rate can be reduced to a certain extent by repeat aspiration, especially in cases of cystic lesions.

COMPETING INTEREST STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

GS designed and conducted the study, performed data analysis, wrote and revised the manuscript. AJ performed literature search, helped in writing and review of the manuscript. SKY performed literature search, data analysis and reviewed the manuscript. RG conceived and designed the study, helped in data analysis and reviewed the manuscript. NS helped in conduct of the study and reviewed the manuscript. SS conceptualized and designed the study, guided the conduct of the study, and helped in draft and critical review of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

This study was conducted with approval from the Institutional Review Board of the institution associated with this study. Authors take responsibility to maintain relevant documentation in this respect.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS (IN ALPHABETIC ORDER)

ACC – Adenoid cystic carcinoma

AUS – Atypia of undetermined significance

EMC – Epithelial myoepithelial carcinoma

FNA – Fine needle aspiration

FNAC – Fine needle aspiration cytology

LEL – Lymphoepithelial lesion

MECa – Mucoepidermoid carcinoma

MSRSGC – Milan system of reporting salivary gland cytology

PA – Pleomorphic adenoma

PLGA – Pleomorphic low-grade adenocarcinoma

ROM – Risk of malignancy

SFM – Suspicious for malignancy

SGN – SSalivary gland neoplasm

SUMP – SSalivary gland neoplasm of uncertain malignant potential

WT – Warthin’s tumor.

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double-blind model (the authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

References

- Clinicopathological analysis of salivary gland tumors over a 15-year period. Braz Oral Res. 2016;30:e2.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fine-needle aspiration biopsy of salivary gland lesions. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2015;139:1491-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Impact on clinical follow-up of the milan system for salivary gland cytology: A comparison with a traditional diagnostic classification. Cytopathology. 2018;29:335-42.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Relative accuracy of fine needle aspiration and frozen section in the diagnosis of lesions of the parotid gland. Head Neck. 2005;27:217-23.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The impact of FNAC in the management of salivary gland lesions: Institutional experiences leading to a risk-based classification scheme. Cancer Cytopathol. 2016;124:388-96.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salivary gland FNA cytology: Role as a triage tool and an approach to pitfalls in cytomorphology. Cytopathology. 2016;27:91-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine-needle aspiration of salivary gland lesions. Comparison with frozen sections and histologic findings. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1987;111:346-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology: Definitions, Criteria, and Explanatory Notes. 2018

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The Bethesda System for Reporting Cervical Cytology: Definitions, Criteria, and Explanatory Notes (3rd ed). New York: Springer; 2015.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The Milan system for reporting salivary gland cytopathology In: William CF, Esther DR, eds. The Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology. American Society of Cytopathology (1st ed). Switzerland: Springer International Publishing AG; 2018. p. :2-4.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Milan system for reporting salivary gland cytopathology: An experience with the implication for risk of malignancy. J Cytol. 2019;36:160-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effectuation to cognize malignancy risk and accuracy of fine needle aspiration cytology in salivary gland using “Milan system for reporting salivary gland cytopathology”: A 2-years retrospective study in academic institution. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2019;62:11-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Application of the Milan system for reporting salivary gland cytopathology: A retrospective 12-year bi-institutional study. Am J Clin Pathol. 2019;151:613-21.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Application of the Milan system of reporting salivary cytopathology-a retrospective cytohistological correlation study. J NTR Univ Health Sci. 2019;8:11-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine needle aspiration cytology of salivary gland lesions: Study in a tertiary care hospital of North Bihar. Int J Res Med Sci. 2016;4:3869-72.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fine needle aspiration cytology in diagnosis of salivary gland lesions: A study with histologic comparison. Cytojournal. 2013;10:5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine-needle aspiration biopsy of the salivary glands. Pathol Annu. 1992;27(2):213-45.

- [Google Scholar]

- A review of research on cytological approach in salivary gland masses. Indian J Dent Res. 2018;29:93-106.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine needle aspiration cytology of salivary gland lesions with histopathological correlation-a two year study. Int J Healthc Biomed Res. 2015;3:91-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnostic role of FNAC in salivary gland lesions and its histopathological correlation. Indian J Pathol Oncol. 2016;3:372-5.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Three-year cytohistological correlation of salivary gland FNA cytology at a tertiary center with the application of the Milan system for risk stratification. Cancer Cytopathol. 2017;125:767-75.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The role of the Milan system for reporting salivary gland cytopathology: A 5-year institutional experience. Cancer Cytopathol. 2018;8:541-51.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northern Italy in the American South: Assessing interobserver reliability within the Milan system for reporting salivary gland cytopathology. Cancer Cytopathol. 2018;126:390-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risk stratification and clinical outcome in the atypia of undetermined significance category in the Milan system for reporting salivary gland cytopathology. Cancer Cytopathol. 2020;129:132-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FNAC of salivary gland lesions with histopathological correlation. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;58:246-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnostic reliability of FNAC for salivary gland swellings: A comparative study. Diagn Cytopathol. 2010;38:499-504.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risk of malignancy associated with cytomorphology subtypes in the salivary gland neoplasm of uncertain malignant potential (SUMP) category in the Milan system: A bi-institutional study. Cancer Cytopathol. 2019;127:377-89.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine-needle aspiration cytology of salivary gland lesions: A revised classification based on “Milan system”-4 years experience of tertiary care cancer center of South India. J Cytol. 2020;37:12-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salivary gland tumor fine needle aspiration cytology. A proposal for a risk stratification classification. Am J Clin Pathol. 2015;143:839-53.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epithelial myoepithelial carcinoma of the parotid gland with malignant ductal and myoepithelial components arising in a pleomorphic adenoma: A case report with cytologic, histologic and immunohistochemical correlation. Acta Cytol. 2007;51:807-13.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]